Blue Music

/

Kind of Blue, 50th Anniversary Collector's Edition

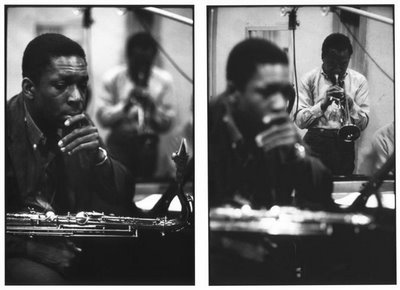

Miles DavisColumbia/Legacy, 2008“Listen,” Miles Davis commands in the terse first line of his autobiography. The one-word sentence perfectly conveys the trumpeter’s assurance that he deserved to be heard; he thought few other musicians merited similar consideration. With simultaneous concision and derision, Davis often asked, “So what?” He provocatively invites his own challenge by using the two words as the title for the first track on Kind of Blue, raising the question: So what makes his much lauded album such a big deal? Davis played with Charlie Parker and the giants of bebop in the mid-1940s before going in a different direction with his own groups afterwards, moving through the stripped down sound of cool jazz, the attempt to blend jazz and classical music, the expansiveness of modal jazz, the polarizing electrified fusion of jazz with rock and roll. But Kind of Blue stands out, admired by musicians, celebrated by critics and enjoyed by both die-hard jazz fanatics and casual listeners.Why does this single record receive so much adulation?The almost ostentatiously extravagant Columbia Records/Legacy Recording 50th Anniversary Collector’s Edition of the album hazards multiple possible answers. Columbia – Davis’s label for much of his career – obviously concluded that Davis and his group had visual as well as aural appeal. It packaged the music with eight-by-ten-inch black and white photos of the players: John Coltrane contemplating his tenor saxophone as Davis plays in the background; Davis seated on a stool seemingly listening closely to something outside the frame (as in the image on the back of the original album jacket); the band leader leaning over the shoulder of pianist and close collaborator Bill Evans, perhaps reviewing charts made that morning, while bassist Paul Chambers stands behind them; Davis conversing with alto saxophonist Julian “Cannonball” Adderley with Evans listening on one side as Coltrane plays on the other; a smiling Davis at a microphone; a focused Davis with horn to his lips. (Wynton Kelly, one of the two pianists on the album, and drummer Jimmy Cobb do not make the montage, though the box set’s heavily illustrated 60-page, 12-inch by 12-inch hardcover documents their involvement.) In case these samples from the three rolls of film Columbia staff photographer Dan Hunstein took during the making of Kind of Blue do not satisfy the memorabilia collector, the dark blue slipcase also holds a poster showing Davis from multiple angles, as if captured in dressing room mirrors.

| Funny man and jazz fan Bill Cosby confirms the importance of Davis’s look in Celebrating a Masterpiece: Kind of Blue, a 55-minute documentary on the DVD that accompanies the anniversary reissue. He describes how he and his friends admired the horn player’s sharp suits and sought to emulate his style. As journalist Ed Bradley of 60 Minutes puts it, Davis was “the essence of hipness.” |  |

The fashions would not have mattered to anyone without the music made by the men in the pictures, of course, and Cosby comments on this too. Davis recorded Kind of Blue fifteen years after coming to New York City to study at Julliard in 1944. When he signed with Columbia in the mid-1950s, his quintet already included Chambers and Coltrane but had a different pianist and drummer. Lineup reshuffling happened regularly. Evans had joined and left the band, but agreed to return for Kind of Blue. Coltrane had sabbaticaled for a stint with pianist Thelonious Monk. Hinting at the sort of obsessive scrutiny by fans that became part of Davis’s legacy, Cosby says jazz aficionados worried about the possible effect of every real and rumored lineup change. Kind of Blue reassured those who took Miles as a synonym for cool that Davis knew exactly what he was doing. “Every time he made a change, it was right,” Cosby concludes. By the time of Kind of Blue, Cobb was behind the drum set and alto saxophonist Julian “Cannonball” Adderley made the group a sextet. Although Kelly was the pianist in Davis’s working band at the time, he plays on only one track; Evans, plays on the others.

|

As the presence of two pianists suggests, Kind of Blue captured the band at another moment of transition. Sessions on March 2 and April 22 respectively yielded the two sides of the original Kind of Blue twelve-inch (which a 180-gram blue vinyl platter in the anniversary package reproduces). Davis would not have been able to make the same record with the same men much sooner or later. |

Another contemporary recording shows the extent and frequency of personnel churning behind Davis. Around the same time that Sony (Columbia’s parent company) issued the deluxe edition of Kind of Blue, the small Acrobat label released Broadcast Sessions 1958-59, which preserves short live sets from radio and television programs aired in the months preceding the making of the famous album. One series of songs from May 1958 has much of the Kind of Blue lineup with Evans on piano, but with a different drummer and before Adderley joined the band. Six months later, Cobb is drumming and Adderley has added his alto, but a pre-Kind of Blue band member sits at the keyboards. A jam session on another date includes several horn players backed by a visiting team of percussionists – not Davis’s regular band. By January 1959, Davis has the sextet with Kelly in place.As usual, Davis would not keep the same working band for long. At about the same time as the Kind of Blue sessions, Coltrane started making Giant Steps with sidemen from Davis’s then-current group. The one member who might rival Davis for the “essence of jazz” title saxophonist Dave Liebman later bestowed on the trumpeter, Coltrane recorded the majority of the album as it was released in 1960 on May 4, 1959, a fortnight after finishing Kind of Blue. He recorded some subsequently issued alternate takes in between the Kind of Blue sessions on April 1. (The next day, the Davis group with Kelly at the piano and without Adderley recorded “So What” for the CBS television show Robert Herridge Theater. The anniversary DVD also includes the 26-minute-long episode, which also presents members of the group backed by an orchestra conducted by Gil Evans performing three songs from the 1957 album Miles Ahead.) With his first Atlantic Records album, Coltrane started moving out on his own. He agreed to tour with Davis after Kind of Blue came out, but he told the trumpeter before they left for Europe that he was leaving the band.Coltrane was not the only one ready to go his own way. Evans, who thought he deserved writing credit for Kind of Blue that Davis adamantly refused to grant, did not work with Davis again. Adderley left soon after the album’s release. Chambers and Kelly left in early 1963, and Cobb soon joined them to form a trio.All but one of the players died long before Kind of Blue reached the half-century mark. Coltrane’s liver cancer killed him in 1967, two years before Kind of Blue reached its tenth anniversary, the year Chambers died of tuberculosis. Both Kelly and Adderley died in the early 1970s. After decades of drug abuse, Evans died in 1980. Only two members saw the record’s twenty-fifth anniversary – Davis (who died a couple years after Kind of Blue hit thirty) and Cobb (who alone survived to see its fiftieth).Neither the rareness of work by the short-lived band nor the poignancy of talented musicians dying young explains Kind of Blue’s enduring fascination. Herbie Hancock, the celebratory documentary’s most insightful interpreter of the record, instead finds the key in the players’ contrasting styles. The alumnus of a later Davis group says Kelly provides “the perfect foil for Miles’s sword.” Adderley’s joyful sound contrasts with the darkness of Coltrane and Evans, whose “gorgeous” instrumental touch especially impresses his fellow pianist.Davis’s and Coltrane’s respective landmark recordings from 1959 highlight their distinct ways of playing. “So What” and “Giant Steps,” among the most well-known and influential songs in jazz, resulted from two very different compositional experiments. Davis made music from sketches and modes, but created a profound “vehicle for expression” instead of “an academic exercise,” Hancock testifies. The result is stunning simplicity, both harmonically and melodically, on a record that through “an economy of means” sounds “fine tuned without being rigid.” Coltrane built his song, with a tempo much faster than Davis’s, on chord changes. “I’m worried that sometimes what I’m doing sounds like just academic exercises,” Coltrane said of Giant Steps, “and I’m trying more and more to make it sound prettier.” Davis could not have made a much prettier album than Kind of Blue.Ashley Kahn, who made a career as a professional record geek, identifies two effects of modal (or scalar) jazz, which defined the period following tone-setting Kind of Blue. First, by taking a step back from the complexities and speed of bebop, it favored simplicity and “a slower, more deliberate pace,” says Kahn, who wrote Kind of Blue: The Making of the Miles Davis Masterpiece soon after the album’s fortieth anniversary and also authored a similar study of Coltrane’s A Love Supreme. Musician David Amram puts it this way in Celebrating a Masterpiece: “Instead of sophisticated chord changes or various harmonies, Miles said…, let’s use a mode or a scale.” Second, modal composition freed musicians from traditional song structures by increasing scale choices, which encouraged lengthened solos. According to saxophonist Jackie McLean, the modal approach lets players “expand a little bit [and] move away from being locked into certain chord progressions.” However, “since 1959, the word modal has become devalued,” Francis Davis explains in his Grammy Award-winning album notes on Kind of Blue turning fifty: “jazz musicians now use it to describe any piece utilizing scales or a minimum of chords.” The term actually applies to music based on specific ancient scales, but “So What,” “All Blues” and especially “Flamenco Sketches” are “the real deal.”

| The studio where Davis’s sextet-plus-one recorded Kind of Blue contributed to its sound. Kahn, who begins his book with a pilgrimage to hear the master tapes for Kind of Blue, which he reveres as holy objects, repeatedly mentions that 30th Street Studio had originally been a church, and several commentators in Celebrating a Masterpiece reminisce about that large, all-wood, high-ceilinged space and its unique properties, especially for capturing acoustic instruments. (Columbia initially used the former Greek Orthodox church to record symphony orchestras.) |  |

Kind of Blue also reflected the atmosphere in the room. Cobb recalled the mood of the sessions as happy and fun, which Hunstein’s photos seem to confirm. Exchanges between the musicians and the producer Irving Townsend, which Kahn transcribes and closely reads in his Kind of Blue and in an essay for the anniversary reissue’s book, include jokes. (Davis: “Can I move this down a little bit?” Adderley: “The union’s gonna bust you.” Townsend: “It’s against policy to move a microphone…”)Such obsessive attention paid to the process of making Kind of Blue can give it a not wholly earned aura of uniqueness. No matter how special 30th Street Studio may have been, many records other than Kind of Blue were made in the same space without ever attaining its rarified stature. Tony Bennett, Rosemary Clooney, Quincy Jones, Frankie Lane, Barbra Streisand and the casts of Broadway musicals, among countless others, also made music there. Part of its reputation, like much else surrounding Davis, results from its absence. It can be bigger than life – a hallowed hall rather than a record label-subsidized workroom – because it no longer exists, having been torn down in the 1980s and replaced by a condominium.Perhaps inevitably for a record that pulled off commercial and artistic success, Kind of Blue became surrounded and at times obscured by mythology. From the very start, those involved in its making contributed to its mystique. In his liner notes and in a later radio interview, Bill Evans says the record consists of first takes, or rather, the first complete recording of each song. (In addition to the false starts and “studio sequences” of chatter between musicians and the producer preceding incomplete takes, the anniversary edition also includes facsimiles of Evans’s handwritten notes). Evans says this (and Davis repeats it) even though the group did complete two versions of “Flamenco Sketches,” the last track of the five on the record.Davis did not use an unprecedented approach, or even an unusual one, for the making of improvisational music. Davis may indeed have “wanted to capture the spirit of discovery in the music,” as Hancock says of Kind of Blue and its (mostly) first takes. Essentially unrehearsed beforehand, Kind of Blue has the “spontaneity and freshness few records have,” in guitarist John Scofield’s assessment. But Kahn points to the earlier, underappreciated soundtrack Davis made for the Louis Malle film Ascenseur pour l’échafaud (Elevator to the Scaffold) at the end of 1957 as the blueprint for the more celebrated later release. Working with French musicians he had not even practiced with, Davis improvised while watching scenes from the picture. He had previously seen a screening, received an explanation of the plot and took some notes, but he entered the session with ideas and themes rather than fully worked out compositions. The taciturn trumpeter gave the musicians “only the most succinct guidance,” bassist Pierre Michelot recalled decades later. In Ascenseur’s liner notes, booking agent Marcel Romano says Davis told him he would not repeat the process. But that’s just what Davis did a little over a year later in New York, with another spur of the moment, quickly made work. Yet Davis had made records in rapid succession with no retakes several times before. Before signing with Columbia, he had a contract with Prestige. Four of the six albums he made for that label emerged from two long sessions with no do-overs.Whatever its contributions to the development of twentieth century music, Kind of Blue gained immediate notice because of racial violence. Around the time of its release in August 1959, Davis performed at Birdland in Manhattan. Standing outside the club smoking a cigarette, he refused to “move along” as ordered by a white policeman. After being beaten and arrested, and having pictures of him in his bloodstained suit printed in newspapers, Davis emerged as a rebel hero, a black man who refused to submit to unjust treatment. Such a reputation helped sell records.Nonetheless, Davis did not share others’ reverence for Kind of Blue, or any other jazz records for that matter. (He listened to classical music at home.) He expressed no interest in revisiting his own recordings, preferring to focus on his next project instead of his last one. “‘So What’ or Kind of Blue – those things are there,” he explained to an interviewer. “They were done in that era, the right hour, the right day, and it happened. It’s over, it’s on the record…. I don’t want you to like me because of Kind of Blue.”

|

And yet people do precisely that. In October 2008, the Recording Industry Association of America certified Kind of Blue as quadruple platinum, meaning more than four million copies of the record had been sold in the United States alone. More than one million of those sales occurred between Kind of Blue’s fortieth and fiftieth anniversaries. Davis’s next project, Sketches of Spain qualified only as a gold record (500,000 copies). Davis’s second most popular title, 1969’s Bitches Brew, achieved about one-quarter the sales of Kind of Blue. |

Even if it was made at precisely the right time, in the right place, with the right people; even if it simultaneously nudged music in a new direction while reimagining what came before; and even if the headline-making attack on Davis and his uncompromising response drew attention to the album at its release, none of these factors, alone or in combination, adequately explains the Kind of Blue phenomenon.As the best-selling album in the genre, Kind of Blue might truly have become the single jazz recording most likely to be owned by someone who possesses no others, but it could not have done so if extensive knowledge of music theory, jazz history, record industry trivia, the group’s personnel and their discographies and admiration for Davis’s suits were required for enjoyment of the music. Kahn concludes his biography of Kind of Blue with an anecdote about witnessing a twenty-something woman purchasing a copy around the time it reached age forty and wondering what motivated her. The album’s place in jazz history, the circumstances surrounding its release and the makeup of the legendary band might go some way toward explaining the record’s appeal to longtime jazz devotees, but probably play little part in twenty-first century purchases. The young shopper might have known none of it. While Davis’s reputation, and Coltrane’s, might contribute to Kind of Blue’s iconic status, the pair did make other records together. And while “the blending of black and white jazz” may be “key to the mystique of the album,” as Gerald Early, another author of a book about Davis, say in his contribution to the commemorative book, only Davis’s picture appears on the album’s cover, so unless that impulse buyer Kahn saw at Tower Records knows which musicians, or which elements of jazz style, were white or black, this explanation has definite limits.The songs themselves are what reward both the rigorous attention of the connoisseur and the disinterested ear of the casual music listener, as masterpieces will do. Kind of Blue is neither a math test nor a history lesson. Although not the first modal jazz record, Kind of Blue managed to be simultaneously adventurous and accessible, respected by musicians and wildly popular. Davis explored pattern-making using a single, central note – the technique he calls “the modal thing” – on Milestones, the record from the year before. With Kind of Blue, Davis lets his guard down, permitting a lyricism at odds with his gruff persona.

| “Everyone likes ‘So What,’” according to Davis. The boast smacks of the self-aggrandizement of Miles: The Autobiography (written with Quincy Troupe), but music itself displays none of the 1989 book’s truculence. From the very beginning, the album takes a much more subtle approach. “So What” starts with a whisper, a quiet and mysterious start involving the simplest of notes, according to Hancock. Chamber’s bass and Evans’s piano provide the distinctive opening. No horns are heard for the tune’s first fifty seconds, and Davis does not enter until a minute and a half has passed. When playing “So What” live, Davis tended to drop the moody bass/piano intro (as in the televised version from the year of its release and in the live version from 1960, previously available as a bootleg, and included on the disc of bonus material in the Columbia/Legacy unit), and his group also accelerates the tempo. Such later interpretations spotlight the lengths Davis went to achieve a subdued sound on Kind of Blue. |  |

In contrast to the four other tracks on the record, “Freddie the Freeloader” has a happy and upbeat sound. A showcase for Wynton Kelly, in his sole contribution to the record, the song “is the blues, but it’s a kind of blues,” Hancock laughingly explains. Cobb’s drums snap alongside Kelly’s jaunty piano playing.“Blue Is Green,” with Davis’s muted and mournful trumpet at the forefront, is eerie, cool. Cobb remembers Davis asking him for a “floating” drum sound, which he creates with brushes. Glancing back to Ascenseur, “Blue Is Green” evokes film noir, conjuring up rain visible in the nimbuses of street lights glowing in the song’s dark night.Though Davis was very much the frontman of his group, he showcased the other musicians, recognizing that he sounded best with strong supporting players. “All Blues” displays Davis’s appreciation of the bass’s ability to do more than provide a rhythmic foundation. Evans also stands out for his fluttering playing early on, which he reprises near the end. Singer/pianist Shirley Horn says “All Blues” sounds like its “going down the road to someplace special, and it really takes you there.” Tension seethes under the song’s smooth surface. The band recorded “All Blue,” the album’s longest and most physically demanding piece, at the end of the second Kind of Blue session. Afterward, a studio sequence reveals, one member sighs with relief and another exclaims: “Damn that’s a hard mother.”With “Flamenco Sketches,” which has no opening melody of theme to play off of, the soloists rely on their own sense of invention, as Kahn explains, and the song’s five scales in a row epitomize modal jazz. While Coltrane plays the simple notes of the major scale, he plays them with unrestrained yet tender passion. More than any other, this track points forward to where Davis wanted to take listeners next.So what is all the fuss about? As Kind of Blue demonstrates, the simplest solutions can be the best. Its narrative arcs slowly from seduction and sweetness to deepening emotional complexity and a look toward the future. “If you want a record to make love to, Kind of Blue is the record,” says Hancock. Kahn compiles multiple testimonials to the album’s “aphrodisiac properties.”Kind of blue indeed.___John G. Rodwan, Jr.’s work has appeared in publications such as The Mailer Review, Spot Literary Magazine, California Literary Review, Slow Trains, The Brooklyn Rail, American Writer, Free Inquiry, the Humanist and the International Labor Office’s Encyclopaedia of Occupational Health and Safety. He has lived in Portland, Oregon; Brooklyn, New York; Geneva, Switzerland; and Detroit, Michigan.Return to the Main Page