Who Moved My Charioteer?

/

How We Decide

By Jonah LehrerHoughton Mifflin Harcourt, 2009

| I have a serious bone to pick with certain members of the medical-, scientific-, and philosophical-history communities. There exists within these communities the notion that history is constantly evolving towards the more correct, that human thought is linearly progressing towards a certain end point. We, as a society, improve upon our ideas by testing hypotheses, discarding false assumptions, embracing correct ones. This is all very well and good for scientific theories – after all, what is science but the continual quest of self-correction? – but for those wishing to investigate the processes of thought that led us to our current state of understanding, this notion of progression misleading, and ignores the potentially fascinating meanderings of history. |  |

Let me take as an example an anatomical historical textbook (about which, the astute reader may recall, I have written before, and written of under strikingly similar circumstances). K.B. Roberts and J.D.W. Tomlinson, in their 1992 Fabric of the Body, concede that our understanding of the geography of the human body has altered drastically over the past several hundred years, and that this alteration was as much the result of society’s changing view of the body as it was the result of medicine’s more-finely-honed investigatory techniques. Yet they insist that the interesting facet in all of this is what precisely our forebears got wrong:

Naked-eye anatomy is a perfectible, descriptive science. From 1500 onwards, in association with printed illustrated texts, the structures of the most, and many of the less, obvious parts of the human body were described and illustrated: the shape of the liver was no longer five-lobed; the heart had two, not three, ventricles; there was no rete mirabile to be seen at the base of the brain; the uterus was not bicornuate; there were three auditory ossicles not two…[sic]. The new anatomy was an improvement over the old; the idea of progress in anatomy is not a whiggish interpretative imposition on this history of that science, not an opinion, but a reality, demonstrable by comparison or illustrations with the actual structures to be seen in dissection, or at operation, or by computerized tomography, or by nuclear magnetic resonance scan.

Roberts and Tomlinson title their sections “The great leap forward” and “The beginnings of factual anatomical illustration” – these examples, along with their above assertion that “anatomy is a perfectible, descriptive science” would indicate that notions about the body prior to 1500 were simply wrong, and that, instead of being something that the local anatomist would himself improve upon with practice, the art of understanding the body’s inner workings required the improvement of history.Again, all very well and good if you want to look at what history got wrong. And I am in no way claiming that the early medieval representations of the human body bear any resemblance to our modern knowledge. But where does this lead us? What new questions does this method of investigation open up? How can we evaluate our current knowledge, keeping the follies of history in mind? As one 17th-century neuro-anatomist lamented, there were as many possible representations or interpretations of the human brain as there were ways to cut into it. Might it not be that our predecessors believed themselves to be correct, their own knowledge to be perfect?And here is where the problem – my bone of contention – arises. The questions to ask are not about what earlier eras got wrong, but about how their thought processes led them to that point. Such interrogation demands that we consider a sort of contextual history, that we comprehend the cultural milieu surrounding, say, scientific or philosophical discoveries. There is a kind of multi-valence of potential meanings, understandings, and ideas circulating in a culture at any particular point in time that a strictly historical interpretation can squash flat.This problem – of asking not why and how but simply what – leads off, settles over, and eventually pervades Jonah Lehrer’s new book, How We Decide. Here, Lehrer tackles the implicit question of the book’s title by asking What do we know about how we decide? But the question Lehrer seems to be striving for but not answering is How has our understanding about how we decide changed and why? (A fitting subtitle for How We Decide would be Why Plato and Everything He Stood for Was Basically Wrong; more on this momentarily.) Lehrer answers the first question but wants to ask the second question. An answer to the second question would make for a new and interesting sort of popular science book. An answer to the first question makes for what How We Decide actually is: a lot of summary but only a little actual probing.Lehrer himself describes his project thus:

This book is about how we make decisions. It is about what happened inside my brain after the engine fire. [Lehrer opens the book with an anecdote about his escapades in a flight simulator.] It is about how the human mind – the most complicated object in the known universe – chooses what to do. It’s about airplane pilots, NFL quarterbacks, television directors, poker players, professional investors, and serial killers, and the decisions they make every day. From the perspective of the brain, there’s a thin line between a good decision and a bad decision, between trying to descend and trying to gain altitude. This book is about that line.

| And Lehrer does what he proposes: he talks about pilots, quarterbacks, directors, poker players, investors, and serial killers, and about what we know about how each of these sets of people makes decisions. Lehrer organizes the book by flipping back and forth between specific anecdotes (about pilots, quarterbacks, etc.) and neurophysiological explanations for what occurs in the brains of those involved in the anecdotes. Disappointingly, there’s no attempt to create a broader through-line or any sort of narrative; the anecdotes don’t necessarily relate topically or historically, and only rarely does one recounting of science build on what we’ve learned in a previous chapter. These are so many case studies, lined up in a row. |  |

This would be fine if all Lehrer wanted to do was exactly what he lays down in the paragraph I quoted above. The big problem is, however, that he aims higher and then doesn’t follow through.Consider the paragraph immediately following the one above:

As long as people have made decisions, they’ve thought about how they make decisions. For centuries, they constructed elaborate theories on decision-making by observing human behavior from the outside. Since the mind was inaccessible – the brain was just a black box – these thinkers were forced to rely on untestable assumptions about what was actually happening inside the head.

Let us leave aside for the moment the problem that the “testable assumption” is a relatively recent development and that the “thinkers” Lehrer references would have had a different methodological approach – namely that of natural philosophy, of laying out the observable and/or logical rules of nature. Lehrer’s chief problem with history is that “these [untestable] assumptions have revolved around a single theme: humans are rational.” Here’s the rub, he argues. “There’s only one problem with this assumption of human rationality: it’s wrong.”And this, in the introduction, not more than a handful of pages into the book, is where things really could start to get interesting. We’re not rational! That’s an enormous claim! (Though economists have been suggesting it for a while, but let that be.) It’s an exciting claim! It’s one that contradicts hundreds, nay, thousands of years of thought, and the philosophies and philosophers whose assumptions underpinned so much of Western thought. Wouldn’t you like to read a book about how we make decisions and how we can’t assume we are rational beings? I certainly would.I think this is the book Lehrer intended to write. This is not the book he actually wrote. Consider, for example, Lehrer’s intriguing point that “[t]he expansion of the frontal cortex during human evolution did not turn us into purely rational creatures, able to ignore our impulses: a significant part of our frontal cortex is involved with emotion.” Part of this frontal cortex (the OFC or orbitofrontal cortex), Lehrer explains, connect the emotions which arise from the more evolutionarily-ancient parts of our brains to the more recently-developed cortical areas, which, it had been assumed, were in charge of imposing rationality upon the emotional human. The idea is that because such a connection exists (between emotional and rational areas of the brain), the notion that reason holds sway over passion might not be anatomically correct.“While Plato and Freud would have guessed that the job of the OFC was to protect us from our emotions, to fortify reason against feeling,” Lehrer argues, “its actual function is precisely the opposite. From the perspective of the human brain, Homo sapiens is the most emotional animal of all.” Sounds reasonable, right? But Lehrer goes no further to illuminate what, again, could be a compelling point. Why were Plato and Freud wrong? Because they didn’t know about the function of this piece of neural anatomy that we now know about – and even if they had known, they would have guessed something different about it entirely. Is it fair to Plato and Freud to lord our modern knowledge over their now-obvious mistakes?The debate Lehrer’s work seems to be seeking to overturn is, ultimately, that of the relationship (if one exists) between rationality and emotion.Now we understand that this binary opposition doesn’t exist, argues Lehrer, that emotion and rationality are intimately intertwined in the decision-making process, that there is no such thing as “pure rationality.” Modern economic theory has, quite recently, embraced this principle; cognitive theory was one step ahead, and so noticed this starting perhaps a decade or so ago. So take that, Plato, Descartes, Jefferson, Freud, and all your friends. You were wrong, we win, QED.Throughout How We Decide, I was anxious to ask Lehrer why, were this idea of rationality/emotion so incorrect, it managed to persist, as a sort of holy grail, through the centuries? It may seem like a small issue, but it underpins, to worrying effect, the whole of Lehrer’s argument (and the argument of his previous, intelligent but flawed, Proust Was a Neuroscientist). At the heart of his new work – indeed, resurfacing with ridiculous frequency throughout it, lest we forget – is the contention that Plato was wrong about the soul. Or the brain. Or the rational soul. Or some conglomeration of the two. Or something else we might recognize as being similar to either one of them.I’m not being deliberately coy here: part of the problem with How We Decide rests in its stubborn refusal to discuss, evaluate, or even (heaven forefend) define the very terms under scrutiny. Lehrer constantly circles back, in one-liners dropped at least once a chapter, to his contention that Plato’s reasoning was flawed. (I will leave the reader to decide whether the ideas of reason or rationality utilized by Plato, Descartes, Jefferson, and Freud, and other casually dismisses thinkers are all identical. Suffice it to say Lehrer thinks they are, and within the space of a single throwaway paragraph says as much.) Let’s have a look at the initial description of this demonized argument:

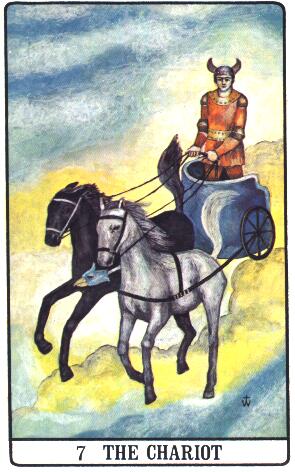

[Plato] liked to imagine the mind as a chariot pulled by two horses. The rational brain, he said, is the charioteer; it holds the reins and decides where the horses run. If the horses get out of control, the charioteer just needs to take out his whip and reassert authority. One of the horses is well bred and well behaved, but even the best charioteer has difficulty controlling the other horse. “He is of an ignoble breed,” Plato wrote. “He has a short bull-neck, a pug nose, black skin, and bloodshot white eyes; companion to wild boasts and indecency, he is shaggy around the ears – deaf as a post – and just barely yields to horsewhip and goad combined.” According to Plato, this obstinate horse represents negative, destructive emotions. The job of the charioteer is to keep the dark horse from running wild and to keep both horses moving forward.With that single metaphor, Plato divided the mind into two separate spheres. The soul was seen as conflicted, torn between reason and emotion. When the driver and horses wanted different things, Plato said, it was essential to listen to the driver. “If the better elements of the mind which lead to order and philosophy prevail,” he wrote, “then we can lead a life here in happiness and harmony, masters of ourselves.” The alternative, he warned, was a life governed by impulsive emotions. If we follow the horses, we will be led like a “fool into the world below.”

In other words, the broad points we can take away from Plato are (1) reason is like a charioteer, emotion is like a bad horse, and (2) emotion = bad and reason = good. Reasonable enough. Until, that is, we start probing the notion upon which Lehrer begins.

|

You don’t have to be a classics scholar to pick out problems with Lehrer’s argument here. Lehrer assumes that Plato identifies the rational soul with the human brain. While it is true that Plato thought the brain was the locus of perception (contra Aristotle, who believed this location to be the heart), the proper identification of soul and brain did not take place until around the 2nd century A.D., when the Greek physician Galen attended to wounded gladiators and realized that damage to their brains corresponded to damage to aspects normally controlled by the soul (like thinking, moving, remembering, and so forth). Even then, Galen was on shaky ground: plenty of his contemporaries were cardiocentrists, maintaining the heart’s superiority in matters of the soul. (In fact, as late as the mid-17th century the admittedly wonky Jean-Baptiste van Helmont would argue that the liver was the seat of the soul.) It was not until relatively recently, in the mid- to late-17th century, that soul and brain came to be roughly synonymous with one another. |

The identity of the brain and rational soul are something Lehrer takes as assumed throughout history – and such an assumption indicates the larger problem in his argument, namely that the historical beliefs concerning the rational soul, which he is so quick (indeed, within the first twenty pages) to discard, had always to do with reason, and that reason and rationality, and the soul, always had to do with the brain.Plato makes the point that, although the charioteers and horses of the gods are “all good themselves and of good ancestry,” in humans “there has been a mixture.” The soul itself (that is, what Lehrer takes to be the rational soul – I assume) comprises the charioteer and horses together: take the one without the other, and you have no soul. Lehrer assumes that one of the horses represents emotion and that the charioteer represents reason. This is perhaps one reading of the case – but what of the other horse? That other horse, obedient and of good breeding, is nevertheless, as Plato puts it, “forcibly constrained by a sense of shame.” When the charioteer and his horses approach a beloved individual, the soul “is afraid and, feeling awe, recoils on his back” because of the conservatism of the shame-filled horse, while the other horse “compels [the other horse and the charioteer] to go towards [the beloved] and to make mention of the delight of sexual gratifications.”The soul comprises the two horses with the charioteer, who may well be the rational soul, but who may also (or instead) be the mind, the identity, the self, or any other number of similar entities. The point is that to posit the charioteer as reason is reductive and problematic, and it disregards Plato’s lesson, which is that right reason involves listening to both horses, both higher and lower impulses. This metaphor is the one to which Lehrer keeps returning as the fundamental incorrect assumption of most of the history of Western thought. If you’re going to try to overturn Plato and the not-inconsiderable assumption that the human mind is reasonable – and especially if you’re going to keep returning to the charioteer metaphor hit your reader on the head with your argument that Plato was wrong – you need to have a more serious consideration of the problem you’re trying to articulate. Again, How We Decide sets out an enormous aim but continually undermines itself by using a rather facile and boring repetition to drive home a point that never actually gets proven.My own point is that, without some clear laying-out of terms, and without a more careful reading of Plato, it becomes difficult, then, to frame an argument based on those terms and based on a brief crib-note knowledge of Plato.Whew! And this all takes place within the first twenty pages of How We Decide. Reason and emotion are Lehrer’s two major players in this book, the two entities at times aligned though mostly at war when we make decisions; why can’t he explain what he (and by extension neuroscience) takes them to be?For he is perfectly capable of such an explanation. Witness, for example, his description of morality:

Morality can be a squishy, vague concept, and yet, at its simplest level, it’s nothing but a series of choices about how we treat other people. When you act in a moral manner – when you recoil from violence, treat others fairly, and help strangers in need – you are making decisions that take people besides yourself into account. You are thinking about the feelings of others, sympathizing with their states of mind.

Excellent! Anyone might agree or disagree with this description of morality, but at least we have something to work with. Psychopaths, Lehrer may then productively go on to explain, lack this ability to sympathize, while autistic patients lack the ability to see others as people at all, and both of these problems have to do with the sense of morality operating in the normal brain. Lehrer does not go so far as to claim that psychopathic and autistic patients could be “cured” by the regulation of their superior temporal sulci (which are parts of our cortex related to action, and which can be found just above the ear) – but that seems to be the logical implication of his argument. Such is the pattern of Lehrer’s chapters: toss out a couple of illustrative stories, note that each demonstrates a kind of decision, point to neuroscientific research that has isolated (apparently) a particular region of the brain responsible for such decision-making, apply the neuroscientific reading to the original stories; throughout, note that Plato and his charioteers got it wrong about reason’s superiority over emotions, whatsoever they may turn out to be.The lack definition of these more overarching terms, however, becomes immensely important when Lehrer probes the depths of choices that seem irrational or dictated by emotion, but that turn out to be correct; or when he suggests that at times the “rational brain” (whatever that is) overthinks, and so leads us to incorrect decisions. Emotion may be a “gut feeling,” but couldn’t that same description apply to rationality? If the rational is the true, the correct, the righteous, and our gut feelings could lead us to that end, might our gut feelings not then be a kind of rationality?(One thing Lehrer never points out, but that I wish he would, is the fact that the term gut feeling derives in part from the fact that there exists a subsection of our nervous system that controls our gastrointestinal system. It’s called the enteric nervous system, and it consists of actual neurons embedded in the lining of our gastrointestinal system; it can operate autonomously, without the aid of our central nervous system; it controls the release of various enzymes necessary for digestion; at, at a more basic level, it tells us when we are full or hungry. Wouldn’t it be interesting – and relevant, in light of modern America’s obesity epidemic – to see what role our enteric nervous system plays in our decision-making?)I'm being a little reductive here, but Lehrer’s clear and cogent descriptions of the relevant neuroscientific work (for more evaluation of which, see below) demand an equally clear and cogent description of the terms of his argument. For these very terms are those with which he is guilty of beating his reader over the head, when he leaves off his description of the work of others and turns to his own argument. Time and again he returns to the (accurate) contention that “the emotional brain…has been exquisitely refined by evolution over the last several hundred million years,” and, of course, that Plato isn’t right, but he doesn’t do much to elaborate.Two key problems of both How We Decide and Proust Was a Neuroscientist are Lehrer’s over-reliance on the repetitive and the formulaic to structure his entire book. (I also have some questions regarding Lehrer’s decision to lump psychologists, behavioral scientists, cognitive theorists, laboratory neuroscientists, and then some, into the category of NEUROSCIENCE. But such a decision is likely not entirely his fault: most American universities group together these at-times-disparate fields of study.)But I don’t want to be entirely negative, and neither should I be. Lehrer has several positive traits working in his favor, which (one would hope) may develop as he progresses in his chosen career. First – and I thought the same of Proust Was a Neuroscientist – Lehrer is quite good at distilling the main points of various complex neuroscientific and cognitive studies, and in translating them (so to speak) for the reader, without even a hint of condescension. His assessments of scientific works both classic and recent are all clear, easy to grasp, and helpful. This, I think, is a rare talent nowadays, particularly as various disciplines constantly partition themselves into ever-more-specific sub-specialties, none of which seems to desire communication with its neighbors, either close or distant (and even the humanities, I regret to report, are subject to this).And, though I objected to this above in its service to his arguments, he is a decent storyteller. Though his approach of simplicity may be overbearing at times, he does strive to draw his readers into the heat and thrust of whatever narrative he has at hand. The best examples of this talent are in his introduction, where he details his own attempts to land a malfunctioning plane in a flight simulator, and in his final chapter, where he follows Stanford particle physicist Michael Binger through his (improbable, but cogently explained by both Binger and Lehrer) rise to the upper echelons of Texas hold’em competition. Here, an excerpt from the latter:

As the days pass, the weak players are ruthlessly culled from the tournament [the World Series of Poker]. It’s like natural selection on fast-forward. The tournament doesn’t end for the night until more than half of the players have been eliminated, so it’s not unusual for the nights to last until two or three in the morning. (“Learning how to become nocturnal is part of the challenge,” Binger says.) By the fourth day, even the skilled survivors are beginning to look a little worn out from the struggle. Their faces are masks of fatigue and stubble, and their eyes have the faraway look of an adrenaline hangover. The smell of stale cigarette smoke seems to be a popular deodorant.

Binger feints and thrusts his way to the final table and there forces one of his opponents, through a series of clever bluffs, to withdraw. The game gets played out over a few sections of text, with intervening reminders of Lehrer’s ultimate interest in cognition (e.g., a compelling experiment carried out by a Dutch psychologist to determine how people make decisions when there is an overload of information, like when one is attempting to buy a car). Sprinkled throughout are also succinct reminders of the lessons of previous chapters. In fact, I enjoyed the final chapter more than the rest of the book put together: it was tightly-edited, well-paced, and the occasional sidetracks generated suspense in the overarching narrative of Binger. It makes for compelling reading, even if you are (like me) among the most casual of poker players. I would go so far as to say that, in fact, this final chapter is the most exciting of the entire book. Possibly Lehrer should stick to cognitive analyses of poker games? There’s publishing gold to be struck there, I’d imagine.___Lianne Habinek is a PhD candidate in English literature at Columbia University. She is working on a dissertation about literary metaphor and 17th-century neuroscience.Return to the Main Page