Second Glance: Fatal Beauty

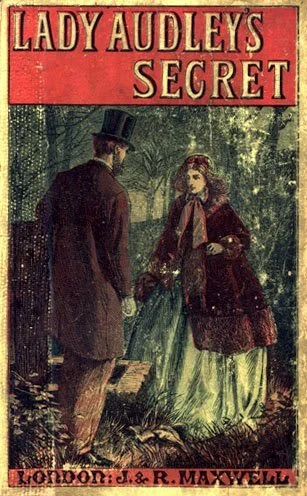

/By Mary Elizabeth Braddon

Drat those women! They’re always reading (or, worse, writing) the wrong books. “The artistic faults of this novel,” writes one discerning critic of a fan favorite, “are as grave as the ethical ones. Combined, they render it one of the most noxious books of modern times.” It’s bad enough such a thing should be published at all, but that the slavering public should bring its shameless authoress both fame and fortune — surely these are the literary end times!

If you’re assuming that his (of course it’s his) target is Fifty Shades of Grey, though, you’re wrong. Our critic is writing in 1865, and the book that has him so exercised is Mary Elizabeth Braddon’s bestselling thriller Lady Audley’s Secret. Today books of its type — lurid, suspenseful, romantic — are ubiquitous. But in its day it was seen as part of a new and disturbing literary genre known as “sensation fiction.” Sensation novels took ingredients familiar from popular Gothic novels like Ann Radcliffe’s The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794) or Matthew Lewis’s The Monk (1796) — secrets, mysteries, illicit desires, lost or stolen identities — and made them contemporary. “Instead of the terrors of ‘Udolpho,’” Henry James observed, “we were treated to the terrors of the cheerful country house and busy London lodgings. And there is no doubt that these were infinitely the more terrible.” Why? Because the dangers they depicted were no longer at a safe remove of both time and geography but right now, and right next door.

Still, the scary possibility that your seemingly amiable neighbors have skeletons in their closets doesn’t entirely account for the intense hostility aroused by sensation fiction. “Works of this class,” raged one critic, are “indications of a wide-spread corruption, of which they are in part both the effect and the cause; called into existence to supply the cravings of a diseased appetite.” “No discriminating reader,” says another, “ever laid down these volumes without regretting that he had taken them up”; and yet another, “their true place in literature … is not above the basement.” It’s clearly not just literary standards that they feel are collapsing but the whole social order: Braddon has “succeeded in making the literature of the Kitchen the favourite reading of the Drawing room,” is the appalled lament.

It didn’t help that Braddon herself was not a respectable figure: a stage actress before she became a lady novelist, she also had a long-running affair and numerous children with her married publisher, John Maxwell (whose legal wife, sensationally enough, was confined to an asylum). But George Eliot’s career showed that morally serious writing could overcome morally difficult living: the author of Middlemarch also cohabited with a married man, after all, but nobody accused her of pandering to diseased appetites, even though you will find blackmail, seduction, betrayal, and murder in her novels. Something about sensation novels in general and Lady Audley’s Secret in particular sent a special frisson of mingled distaste and horror through the literary establishment — but what?

The novel begins innocently enough by introducing us to Lady Audley — sweet, golden-haired, and beloved by all, especially her elderly husband, Sir Michael Audley, who became enamoured of her when she was just the lowly governess Miss Graham. And who could blame him?

Wherever she went she seemed to take joy and brightness with her. In the cottages of the poor her fair face shone like a sunbeam. . . . Miss Lucy Graham was blessed with that magic power of fascination by which a woman can charm with a word or intoxicate with a smile. Everyone loved, admired, and praised her . . . everybody, high and low, united in declaring that Lucy Graham was the sweetest girl that ever lived.

Lucy embodies the idealized vision of Victorian womanhood that came to be known as “the angel in the house.” But we get early signs that all with her is not quite as it seems. When Sir Michael proposes, for instance, she responds rather differently than the fond old man expects, falling on her knees before him and imploring him not to “ask too much of me”: “Remember what my life has been,” she exclaims; her history of poverty, she tells him, means “I cannot be disinterested; I cannot be blind to the advantages of such an alliance. I cannot, I cannot!”

This blunt admission of self-interest rather spoils the mood, but Sir Michael honorably stands by his proposal. “I dare say I am a romantic old fool,” he tells her, “but if you do not dislike me, and if you do not love anyone else, I see no reason why we should not make a very happy couple.” Still, he leaves a little disappointed that he is to be “married for his fortune and his position.” Lucy, on the other hand, knows that she has done well: “No more dependence, no more drudgery, no more humiliations . . . every trace of the old life melted away — every clue to identity buried and forgotten — except these.” And she sits quietly contemplating these enigmatic clues: “a ring wrapped in an oblong piece of paper — the paper partly printed, partly written, yellow with age, and crumpled with much folding.”

On that enticingly mysterious note, Braddon cuts away to a second plotline, this one the story of stalwart George Talboys, who is returning from an expedition to Australia where he has been prospecting for gold. All he can think of as the ship makes its way into London is his sweet, golden-haired wife Helen. Cut off by his wealthy father for marrying beneath him, George was not able to support her comfortably; their poverty and her misery inspired him to leave her and their infant son behind and go off to make his fortune. He hasn’t written her so much as a line in all the years he’s been away, but the thought of her has sustained him:

I clung to the memory of my darling, and the trust that I had in her love and truth, as the one keystone that kept the fabric of my past life together — the one star that lit the thick black darkness of the future.

Now a rich man, he eagerly anticipates his reunion with this “girl whose heart is as true as the light of heaven.” Imagine his horror, then, when soon after his arrival in London he learns of her untimely death.George gets this terrible news while in the company of his dear friend, Robert Audley — the nephew, as it happens, of that same Sir Michael Audley who has recently married the sweet, golden-haired Lucy Graham. To cheer up the devastated widower, Robert invites him to come along on a visit to Audley Court, where he hopes finally to meet “this fair-haired paragon, my new aunt.” Aunt Lucy is a bit evasive, however: it’s almost as if she doesn’t want to meet her nephew’s good friend George Talboys face to face. So George and Robert end up touring Audley Court in the company of Robert’s cousin, Alicia.

Alicia hasn’t been altogether thrilled at gaining a beautiful blond step-mother barely older than she is. She takes malicious pleasure, therefore, in leading the young men through a secret tunnel into Lucy’s locked boudoir, where she shows the visitors a painting of Lady Audley commissioned by her doting husband. “The painter,” remarks our narrator, “must have been a pre-Raphaelite,” as only a member of that subversive artistic brotherhood — known for their fascination with overtly sensual and morally problematic women — could have created a portrait at once so gorgeous and so discomfiting:

It was so like and yet so unlike; it was as if you had burned strange-coloured fires before my lady’s face, and by their influence brought out new lines and new expressions never seen in it before. The perfection of feature, the brilliancy of colouring, were there; but I suppose the painter had copied quaint medieval monstrosities until his brain had grown bewildered, for my lady, in his portrait of her, had something of the aspect of a beautiful fiend.

What does this prescient artist see that ordinary mortals can’t? And what does George Talboys see, as he sits before the portrait “for a quarter of an hour without uttering a word, only staring blankly at the painted canvas”?

If you’ve already guessed the secret — that George’s adored bride Helen did not actually die but has created a new life for herself as Lucy Graham, now Lucy Audley — don’t be too pleased with yourself. For one thing, the clues are hardly subtle! And for another, there’s more to the mystery of Lady Audley than that. Don’t be too sure, either, that the artist is right about Lucy’s fiendish character, or that we should be on George’s side against the wife who has so calculatedly betrayed him. After all, George did abandon her — and now Robert and George have entered Lady Audley’s room illicitly, violating her carefully-guarded privacy and threatening her with exposure: whatever the resulting revelations and repercussions, at this point they can’t really claim the moral high ground.

The next day George goes, alone, to Audley Court, where he’s told he’ll find my Lady walking in the grounds. When he doesn’t return, Robert is first puzzled then panicked. Where can George have gone? And what has caused the bruises — “four slender, purple marks, such as might have been made by the four fingers of a powerful hand” — on Lady Audley’s arm? These mysteries initiate a transformation in the previously indolent Robert Audley, who is galvanized into first frantic then relentless action on behalf of the dear friend he comes to believe has met a violent end at the hands of a perfidious woman determined to preserve her new identity at all costs. A suspenseful cat-and-mouse game ensues between him and his beautiful and ruthless antagonist. Will she get away with her audacious reinvention of herself, and how far will she go to protect it? Or will he prevail in his quest to prove her real identity and achieve justice for his lost friend?

More interesting than finding out whether Lady Audley will get away with her daring scheme, however, is figuring out whether she should get away with it — and wondering why it matters quite so much to Robert. “Why have you tormented me so?” she demands as their contest reaches its crisis: “Why could you not let me alone? What harm have I ever done you that you should make yourself my persecutor?”

The answer might seem obvious. Certainly it does to Robert, who sees himself as “a pitiless embodiment of justice, a cruel instrument of retribution” — not just for George’s death but for the attempts Lady Audley makes to discredit and destroy Robert himself. She points out that his success will be his beloved uncle’s downfall: “Those who strike at me must strike through him,” she warns him, as she “defied him with her quiet smile — a smile of fatal beauty.” She tries to convince her trusting husband that “Robert Audley has thought of his friend’s disappearance until the one idea has done its fatal and unhealthy work,” becoming a “monomania” that has distorted his reason. And when these subtler tactics do not put an end to his pursuit, she makes a stealthy nocturnal visit to his inn, locks the door of his room from the outside, and sets the place on fire. Surely she is, as Robert pronounces, “the demoniac incarnation of some evil principle.”

But if Robert were as noble and she as irredeemably evil as he presumes, the novel would be both duller and less subversive. Like the critics who objected so vehemently to Braddon’s success, Robert is a great defender of the status quo, and he particularly dislikes women who “don’t know what it is to be quiet.” “I hate women,” he rants;

They’re bold, brazen, abominable creatures, invented for the annoyance and destruction of their superiors. Look at this business of poor George’s! It’s all woman’s work from one end to the other. He marries a woman, and his father casts him off . . . He hears of the woman’s death, and he breaks his heart — his good, honest, manly heart, worth a million of the treacherous lumps of self-interest and mercenary calculation which beat in women’s breasts. He goes to a woman’s house and he is never seen alive again.

Suddenly Robert doesn’t seem so heroic, does he? Of course, his misogyny is not in itself any justification for the growing list of crimes of which Lady Audley stands accused. But what if she’s acting in self-defense, not so much against George or Robert in particular but against the entire sexist system they represent and defend? Before her marriage, we learn, her drunken father had been prepared to sell her “to the highest bidder”; her husband abandoned her “with no protector … and with a child to support”; the restrictions on her education and opportunities as a woman made her beauty her only asset and marriage her only avenue to prosperity — as she is well aware. “I learned,” as she explains to her accusers,

that my ultimate fate in life depended upon my marriage, and I concluded that if I was indeed prettier than my schoofellows, I ought to marry better than any of them.

In this context, her bigamous second marriage is just a good career move, a well-earned promotion from a life of “trials, vexations, humiliations, deprivations.” She and George both, in their own ways, went digging for gold in their allotted territories: why should she be judged harshly for her equivalent success? And when George’s unexpected return from Australia threatens her hard-won security, why shouldn’t she fight to protect it?

She has a get-out-of-jail-free card too: whatever she may or may not have done, she can’t be held responsible for it. “It is a great triumph, is it not?” she demands of Robert when he finally has her cornered; “a wonderful victory! You have used your cool, calculating, frigid, luminous intellect to a noble purpose. You have conquered — a MADWOMAN!” This “hereditary taint” of madness is her real secret, and as she hopes, revealing it to Robert saves her from her crimes’ worst consequences, not because it turns his horror to compassion but because it gives him an excuse to avoid the scandal that would follow on a trial.

But there’s another way that her insanity plea plays right into Robert’s hands: it means he doesn’t have to take seriously her critique of women’s vulnerability in a man’s world. If rebellion against patriarchy equals madness, the political is only personal, and there’s no need to do any subtle moral calculus to decide whether bigamy, arson, and murder are in any way proportionate responses to the cruelties and injustices she has faced. All such questions can be safely locked away with her in the shabby maison de santé to which she is eventually confined. “Has my beauty brought me to this?” exclaims Lady Audley incredulously as she surveys the “faded splendor” of her final home; “I had better have given up at once, since this was to be the end.”

This sad finale to Lady Audley’s brilliant career as a social-climbing femme fatale should reassure even the most conservative reader. And it would, if Lady Audley’s Secret itself didn’t raise doubts about its own cautionary conclusions. Even if Robert dismisses her self-justifications as irrational raving, for one thing, they do actually make a lot of sense — enough that even the doctor who ultimately commits her initially demurs. “There is no evidence of madness in anything she has done,” he tells Robert;

She ran away from her home, because her home was not a pleasant one, and she left it in the hope of finding a better. There is no madness in that. She committed the crime of bigamy, because by that crime she obtained fortune and position. There is no madness in that.

Even her subsequent crimes, shocking as they are, show “coolness and deliberation,” not madness. That the doctor is eventually won over by Robert’s urgency to “save our stainless name from degradation and shame” only gives us more reason to see Lady Audley not as mad, but as angry at the men who have from start to finish conspired to thwart her ambitions.“

Lady Audley’s real secret,” argues feminist critic Elaine Showalter, “is that she is sane and, moreover, representative”: representative of thousands of Victorian women raging inwardly about being treated like dolls rather than adults; revered in theory but in practice denied rights, education, and opportunity; expected to radiate grace and charm while condemned to lives of dependency and subordination. The most terrifying possibility Lady Audley’s Secret presents is that behind the smiling facade of the angel in the house there lurks a rebellious devil, eager to be revenged on the patriarchy. Even more startling, the chapter in which Lady Audley meets her doom is called “Buried Alive,” a strong hint that our sympathies should really be with her, not the novel’s righteous and triumphant hero. When such a book proves extremely popular among the very readers you hope will stay quietly in their place? Now that’s sensational! No wonder the old men were quaking in their boots.

Rohan Maitzen teaches in the English Department at Dalhousie University in Halifax, Nova Scotia. She was an editor at Open Letters Monthly and blogs at Novel Readings.