Our Editions, Ourselves

/Middlemarch

By George Eliot (Foreword by Rebecca Mead)

Penguin Classics Deluxe Edition

Penguin, 2015

All avid readers know that our bookshelves are extensions of our identities: our books reflect our histories, our aspirations, our passions, even our failures (don’t we all hang on to at least one long-unread book because we are definitely going to read it some day — just not today, or, so far, any day?) So what does it signal about you if you have multiple copies of the same book on your shelf? Obsession? Acquisitiveness? Or just absent-mindedness? For an English professor like me, it doesn’t usually mean much except that the book in question is one you call on often for teaching or research. But even that is revealing, when you think about it: why this book, and not some other book — the one your colleague down the hall collects, for instance? And even when the accumulation of copies is, in context, entirely unremarkable, your choice of specific editions still invites scrutiny: what do these variations on the same text reveal about the equally varied purposes of your reading? For all readers, what stories do our copies of particular books tell about our relationship with them?

For me, these are all questions provoked by the ten copies of George Eliot’s Middlemarch I currently own, which do indeed tell a story. I first bought this great novel in an unassuming Pan Classics edition. All I have left of that copy is a scrap of the front matter. But I know that I bought it in London: I am certain of this both because the occasion was memorable — it was late March 1986 and I was shopping for books before leaving England for the Continent, on the second leg of a six-month backpacking tour, anticipating long hours on the train and long nights in youth hostels — and because I wrote that information on the page before I tore it out as a souvenir. I know, too, that I finished reading it on April 16, 1986, in Lagos, Portugal, because I recorded the event in my journal. My remarks on the novel are interesting only because (though I had no inkling of this at the time) they were the very first in what would become a long list of commentaries on Eliot’s masterpiece:

Finished reading ‘Middlemarch.’ Really enjoyed reading it, more so once I was deep enough into it to get tied up emotionally with the various people - it took me a while to be able to easily read her style.

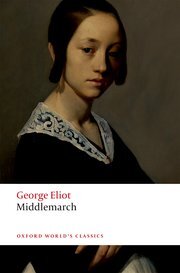

It wasn’t easy to find an image of this edition, which is long out of print, but I recognized it immediately when I saw it. I’m sure the cover was a key reason that I plucked it off the shelf: knowing nothing else about George Eliot or Middlemarch, I would have seen a kindred spirit in that grave young girl clutching her book. I haven’t been able to recover the back cover copy from that edition: what did it say about the plot of this famously expansive novel that sealed the deal? I can easily imagine my 18-year-old self reading something like this description (pulled from Goodreads) and saying ‘yes, this is for me’:

'We believe in her as in a woman we might providentially meet some fine day when we should find ourselves doubting of the immortality of the soul,' wrote Henry James of Dorothea Brooke, who shares with the young doctor Tertius Lydgate not only a central role in Middlemarch but also a fervent conviction that life should be heroic.By the time the novel appeared to tremendous popular and critical acclaim in 1871-2, George Eliot was recognized as England's finest living novelist. It was her ambition to create a world and portray a whole community — tradespeople, middle classes, country gentry — in the rising provincial town of Middlemarch, circa 1830. Vast and crowded, rich in narrative irony and suspense, Middlemarch is richer still in character, in its sense of how individual destinies are shaped by and shape the community, and in the great art that enlarges the reader's sympathy and imagination. It is truly, as Virginia Woolf famously remarked, 'one of the few English novels written for grown-up people'.

A young woman on a heroic quest, the promise of a whole world in one book, and that maddening line about grown-up people, which I would have received as a dare: of course I bought it, and of course I loved it.

I gave my Pan edition away: this was what readers on the road did with their precious portable entertainment in those pre-Internet, pre-iPhone days, sharing and trading and passing it around. But though I left the physical book behind, I carried its memory with me — not so much specifics as a general impression of deep satisfaction. When I reread the novel three years later for an undergraduate course in Victorian fiction, my new copy inherited that aura: remembering pleasure, I anticipated more, and I wasn’t disappointed. If I had come to it without preparation, would I have felt the same?

The Riverside edition we were assigned, ugly and prosaic as it was, would have done little to win me over — but it also put little in the way of my enjoyment: its editor, eminent George Eliot scholar Gordon S. Haight, clearly did not believe readers needed a complex supporting apparatus of explanatory notes and glosses to make their way through Middlemarch. The cover illustration, too, points us away from the novel’s abstract social and philosophical layers and straight towards its emotional climax. An English major by this time, I knew to call the thunderstorm that finally brings the novel’s long-thwarted lovers together an example of the pathetic fallacy — but that didn’t spoil the tender thrill of the moment:

While he was speaking there came a vivid flash of lightning which lit each of them up for the other, and the light seemed to be the terror of a hopeless love. Dorothea darted instantaneously from the window; Will followed her, seizing her hand with a spasmodic movement; and so they stood, with their hands clasped, like two children, looking out on the storm while the thunder gave a tremendous crack and roll above them and the rain began to pour down. . . . It was never known which lips were the first to move towards the other lips, but they kissed tremblingly and then they moved apart.

I bring much more to this moment now than I did at 18 or 21 — that kiss seems much more complicated, opening up nearly as many questions as it resolves. I can’t unlearn what three decades of both study and personal experience have taught me. But I wouldn’t want to, anyway, and besides, my intellectual transformation has not undone the emotional connection I still feel with the novel. When I read Middlemarch today, in fact, I feel a persistent intermingling of thought and feeling that seems just right for Eliot’s fiction: ideas, as she herself wrote, “would hardly be such strong agents unless they were taken in a solvent of feeling.”

All of the copies of Middlemarch I’ve acquired since then have been what are usually referred to as “scholarly editions,” because by the time I’d finished that third-year class on the 19th-century novel, Middlemarch had become, for me, not just another book but my vocation — I had merged, it almost seems now, with that ardent young woman who first caught my eye, only it was she and her book that I clutched to my heart. As I wrote my Honours thesis, then my PhD thesis, my go-to Middlemarch was the well-annotated Penguin Classics version edited by W. J. Harvey (since superseded by Rosemary Ashton’s fine edition). Then when I began teaching Middlemarch regularly myself, I developed a fondness for the neat, reliable, and reasonably priced Oxford World’s Classics editions; I have a stash, now, of teaching copies in varying stages of wear and tear.

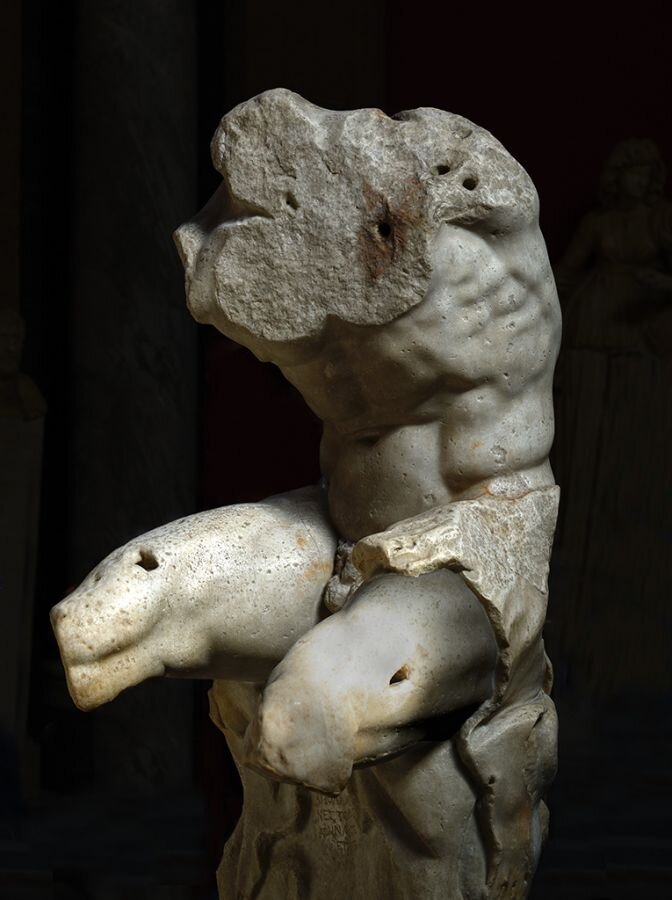

For some classes, however, I have used the excellent Broadview edition instead, which stands out among the others for including a couple of thematically key illustrations. These are particularly illuminating for the scenes in the Vatican, during our heroine Dorothea’s catastrophic honeymoon with the intellectually (and, almost certainly, sexually) impotent scholar Edward Casaubon. It’s one thing to know that his rival, the ardent young Will Ladislaw, is captivated by the sight of Dorothea pausing next to “the reclining Ariadne, then called the Cleopatra,” and another to picture her juxtaposed against this “marble voluptuousness.” The tactile sensuality of the sculpture makes Dorothea’s dissatisfaction anything but abstract. Will himself has re-entered the novel standing next to the Belvedere Torso: if an image of that too were included, the power and significance of sexuality in Eliot’s fiction would be even harder to miss.

Yet at times the quantity of footnotes in the Broadview edition almost overwhelms the text on the pages, and when that happens, the novel looks less and less like something you can just read and more like something you aren’t supposed to, at least, not on your own. Under these conditions, the “solvent of feeling” has to be very strong indeed. And the balance tilts even further towards apparatus and analysis with the Norton Critical edition, which is both an impressive feat of editorial scholarship and a rich compendium of critical insights and trends. I’ve only ever used the Norton in graduate seminars, where the reader’s rigorous detachment is always already assumed.

This catalogue of my editions of Middlemarch says much more about me than about Middlemarch itself, of course, and especially about how my reading life has changed since 1986. One way or another, I’m always reading Middlemarch for work now, so I have almost forgotten what it’s like to think of it just as a novel. I don’t mean that I don’t “really enjoy reading it” any more. If anything, I get more pleasure from it than I possibly could that first time (though I do sometimes think back wistfully to that sun-lit town by the sea). If I didn’t believe that learning more about books — seeing more in them — could enhance our delight in them, I could hardly show up to work every day. That said, my preference for scholarly editions reflects not just my concern to help students with unfamiliar contexts, but also my desire to get in between them and the novels a bit, to interfere with the immediacy of their reading. They are used to reading for feeling, after all; I want to add enough friction to the experience to ensure that they think, too.

Am I doing the right thing, though, in forcing this distance on them? I’ve never doubted it before, but since I received my copy of the new Penguin Deluxe edition, I’ve been wondering.

This new edition is a handsome one indeed, with a heavy cover in an attractive shade of teal, high quality paper and crisp, generously-sized font (Sabon Lt Std, according to the colophon). The cover art is a bit baffling — the first impression it gives is that the novel is about palmistry —but the design is certainly eye-catching and elegant, and it does neatly capture the idea of a novelist who has a whole world in her hands. Strikingly, nothing on the cover, or even the cover flaps, tells you anything about the novel itself: you have to actually open the book to get a sketch of the contents and then two endorsements — the first, inevitably, Woolf’s remark about “grown-up people,” the second Hermione Lee declaring it “the most profound, wise, and absorbing of English novels.”

This set-up suggests a prospective reader very different from the one imagined by the engagingly personal cover of my old Pan Classics edition. Unlike my 18-year-old self, this reader does not need her interest to be caught by either a person or a plot. This is Middlemarch without preliminaries; its appeal is assumed. Middlemarch, we might reasonably infer, is having a moment, something that is also signalled by the choice of Rebecca Mead to write the foreword. Mead’s My Life in Middlemarch was both a memoir and an extended exercise in making Middlemarch (often regarded by the general public as a daunting Everest among classics) familiar and accessible. In it, Mead approached and wrote about Middlemarch simply as a person reading a favorite book, not an expert explicating it. She continues in that vein in her Foreword here, emphasizing the meaning Middlemarch has had for her personally and encouraging new readers “to think of it not as an intimidating, monolithic entity” but as a novel that has the ability to move us “to new understandings of ourselves, and of those people around us.” Presumably this impulse to make Eliot’s novel more user-friendly lies behind the decision to include no notes: “interested readers” are referred to Rosemary Ashton’s standard Penguin Classics edition. (This is not simply a function of the series, as some of the Deluxe Classics — Jane Austen’s Emma, for instance — are fully annotated.)

I stumbled initially over the idea that the “deluxe” version of a novel as rich and complex as Middlemarch included almost nothing but the text itself. There’s no doubt, however, that this is a beautiful book — one that feels luxurious to handle and, more important, one that is inviting to read. Opening it for the first time to the novel’s Prelude, I was drawn in immediately, and the further I read, the happier I felt about it. There were no superscripts or asterisks pointing me elsewhere: there was just page after page of Eliot’s marvellous prose — wise, witty, probing, profound — and chapter after chapter of her multi-faceted story. It was all intimately familiar, but somehow it also felt fresh, in a way that it hasn’t for many years: the book seemed free, as if it too were luxuriating in its big pages and nice font, and in the absence of explanations that always, whatever their intentions, imply that on its own the novel is not enough.

In this edition, Middlemarch is itself again, unencumbered, and there is something wonderful about that. Here is Dorothea, wondering what to do with her life; here is her hilarious uncle, with his “miscellaneous opinions, and uncertain vote”; here, in all his pedantic glory, is her unlikely suitor, Mr. Casaubon: “He has got no good red blood in his body,” says his disappointed rival, Sir James Chettam, to which his sharp-tongued neighbor Mrs. Cadwallader makes the immortal reply, “Somebody put a drop under a magnifying-glass, and it was all semicolons and parentheses.” Here’s the narrator, too, challenging us to follow her in seeing everything from different points of view: “But why always Dorothea?” she demands, and at her urging, and with her help, we turn our attention, and with it our sympathy, away from Dorothea to her gloomy husband — to noble, doomed Dr. Lydgate — to childhood sweethearts Fred Vincy and Mary Garth — to the pathetic moral fraud Mr. Bulstrode — to all those the novel’s Finale so movingly celebrates, “who lived faithfully a hidden life and rest in unvisited tombs.”

Even though by this time not a word of Middlemarch is unfamiliar to me, it turns out that this unexpected “deluxe” edition, in which the novel is actually reduced to its essentials, had the effect on me, though in reverse, that I have always wanted those scholarly editions to have on my students: it disrupted my expectations and made the novel into something new, prompting (even requiring) me to read it differently, more intimately, than I’ve become accustomed to. I’m still not sure I want my students to read it this way, unfiltered — though maybe, in truth, the scope and complexity of Middlemarch are challenging enough to make introducing further obstacles redundant. Maybe, too, they don’t really need the support of the scholarly apparatus: I wonder if more of them would love Middlemarch the way I did when I read it in 1986, perfectly happy in my unknowingness, if they met it in this appealing form. These are questions I will have to think more about before book orders come due for next year. But I do know one thing for sure: ten copies of Middlemarch is enough — at my office. This edition of Middlemarch gets a place on the bookshelves I keep, not as a professor, but as a reader. It’s about time my favorite book came home and stayed.

Rohan Maitzen teaches in the English Department at Dalhousie University. She was an editor at Open Letters Monthly and blogs at Novel Readings; she also created the website Middlemarch for Book Clubs.