One More, Please

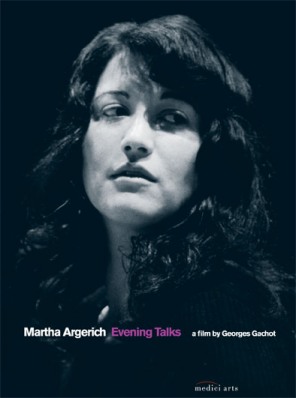

/Martha Argerich: Evening Talks

A film by Georges GachotMedici Arts, 2008Carnegie Hall, October 7, 2008Martha ArgerichPhiladelphia Orchestra, Charles Dutoit conductingIn the last century, there’s hardly been a pianist who has inspired as much yearning on the part of listeners, or of watchers. Martha Argerich, since she appeared on the international stage in 1957, has always left her admirers wanting something. There was her beauty, but it wasn’t just that. She was also idiosyncratic, mysterious and reclusive. Argerich rarely spoke to the press, and what personal details emerged served to lend her an air of instability, and un-attainability (just try seeing her in concert). More than all that, what kept her from fading away was her magnificent way with the piano. Argerich has a technical apparatus only a handful can match. She has a poetic sensitivity, but can be gloriously impulsive, and decidedly muscular. Some of her records are frightening.

| All of her recordings are fascinating, for their nuances and their rarity. Nothing played more than once is ever played the same way, and Argerich’s solo discography is disproportionate to her fame. She returns often to certain pieces, but always with a different conception in mind, or she simply plays on the fly, in the moment. Take one of her favorite pieces, Chopin’s Scherzo in C-sharp minor. She’s recorded it three times. Her second recording, from 1965, is the slowest (though it’s not slow, clocking in at seven minutes flat). It’s heavier and the tone is fuller and deeper than the others. The opening octaves crash with incredible force. This more considered tempo pays off in the wispy descending arpeggios of the central meno mosso. Her tonal shading is remarkable: the figurations dance around the melody to an effect that can be called, without embarrassment, ethereal. |  |

Not many can coax these sounds out of the instrument. But the flipside to Argerich’s impulsiveness that her interest in what she’s playing occasionally wavers from one moment to the next, and that’s the case here. When the octaves return after the middle section, the pace slackens and the rest of the piece makes an underwhelming contrast with its energetic beginning.The third outing was recorded live fourteen years later, at the Concertgebouw in Amsterdam. It’s demonically fast, clocking in at a ludicrous five minutes, forty-five seconds. The opening tempo is marked presto, but Argerich takes it prestissimo mas possible. The meno mosso is beguiling, but Argerich has gone so fast from the start that she can’t slow down enough to let the notes breathe. The coda, one of Chopin’s best, is admittedly thrilling but the final chords are nearly indecipherable at this speed.Her first recording is the tightest all around. It occupies the middle ground between the others: the opening is fast and the dreamy cascading arpeggios are beautiful, if not as evocative as they would be five years later. The technically perilous coda is nearly as demonic as her impulsive live account would be, but it’s more clearly articulated. It’s a desert island recording, to be sure, but why be satisfied with just the one?Argerich in Warsaw, 1965: Chopin’s Scherzo in C-sharp minor, Op.39You never know how Argerich would play on any given night (whereas you could make a good guess with a Maurizio Pollini), but then again she might not play at all. Argerich is notorious for canceling concerts (as this writer knows all too well). And for almost twenty years she didn’t venture into solo repertoire at all, playing and recording nothing but concertos and chamber music. As she explains it in a recent issue of Gramophone,

I really don’t like to go to my own concerts. Alone, I don’t like it. Of course, if I’m with other people it’s different…. But one doesn’t choose to be a performer. One doesn’t choose one’s character…Whenever I’m on my way to a concert I look at all the people and think what’s happening to them? They’ve just finished work and now they’re all off…to the cinema. And I think “Me too!” Exactly. I always want to go to the cinema. Not to my concert. I never think “I am about to play the Liszt Sonata, it’s terrific, I play it wonderfully and I can’t wait to share it with the public.” Never.

Argerich’s discography is fabulous. Only Vladimir Horowitz can match the virtuosity and daredevil tempi of her Rachmaninoff concerto, and she rivals the famous Russian emigrant in Tchaikovsky’s First as well. Her 1977 recording of Chopin’s preludes is the best cycle in existence, and she has a keen insight into Schumann, Ravel and Prokofiev. But releases in the last two decades have been strictly collaborative work. In Shostakovich, Beethoven and Schumann she (and her collaborators) have made some wonderful recordings. There is of course the aforementioned problem. As piano scholar David Dubal once impatiently put it, “In the past decade and a half Argerich has been an exasperating disappointment to her countless admirers who patiently wait for this diva of the piano to perform solo recitals. She well knows that the solo literature should be a concert pianist’s chief activity…”I’d like Argerich to delve into the solo literature as much as anyone, but the condescending paternalism is a bit much. There’s no space in such a view for personal circumstance, which Dubal seems perfectly willing to grant someone else. Horowitz, His favorite pianist (and my own), had no less than three separate retirements. He was plagued by anxiety and psychosomatic problems throughout his career, and in his informative but sycophantic book Evenings with Horowitz, Dubal is rightfully understanding of this. The demands placed upon modern pianists are suffocating: recordings, interviews, dozens of recitals each year. And where has that gotten us? The up and coming pianists of today are mostly boring competition winners – emotionless stenographers with technique and not much else.Dubal did his whining over a decade ago, and in the past few years Argerich has begun to venture onto the stage alone. These are encores or half-recitals – only a portion of a night’s program, and the pieces are familiar: Bach’s second Partita or Scarlatti’s sonata in D minor (you simply must have a recording of her in this; the ’79 recital at the Concertgebouw will do nicely). These are pieces she’s comfortable with, and we can all hope that she’ll give us more.Argerich in 1979: Scarlatti’s Sonata in D minor, K141That Gramophone interview was a rare one, as the magazine took pains to note. It is in this context that the new DVD, Martha Argerich: Evening Talks, comes to American shores. Georges Gachot conducted these interviews in 2002, but this is its first appearance in the New World. Gachot followed the pianist around, filming her at rehearsals, in concert and for an interview. It’s a splendid production. Argerich talks at length about her musical development, her influences, and her favorite music, which the director makes sure is never far from our ears. The interview begins with Argerich’s first formative experience:

It was probably the strongest musical impression in my life. I was six. I remember. It was Beethoven’s 4th concerto. …It was astounding. It was Arrau playing. My mother always took me to concerts. They started late in Argentina, when I was a child. I was sleepy. But when I heard those trills in the 2nd movement, it gave me chills. That concerto really marked me. It was the first strong musical impression I ever had. I already played piano. But it hadn’t done anything to me. I hadn’t had that shock. That electric shock.... Even more than that. I was dozing off and suddenly…that! It was extraordinary…an incredible feeling. |

|

Gachot has the Beethoven Fourth playing in the background while his subject is talking, and right there he pauses the interview so we can hear those trills. When they subside, the pianist tells us “But I don’t play that concerto. I’m afraid to. I don’t know what would happen. It’s so important to me!” This care and craft suffuse the video.The interview inevitably turns to Argerich’s fear of solo recitals. She’s had panic attacks before concerts since she won her first competition as a “terribly shy” girl of 16. A paralyzing fear would grip her before she had to perform. “The reality has nothing to do with the imagination. The imagination is much worse...And then the moment you are there it is much easier because you are doing it, like everything.” This is why today, when persuaded to do an encore, she’ll rush to the piano and begin playing immediately, even while the audience is still clapping. “Why do I like to play with others? Because alone I feel as if…I can’t look right or left. Strange, isn’t it? …Because I can’t look around, I don’t move naturally. When I move with the others, the orchestra, I feel people move, I look, I move too. I’m much more natural!”We also get a good idea of she feels about composers she plays, and perhaps of how other pianists see the music they love. “I have a thing with Schumann…a real affinity…I have an image that’s not textual, rather, it’s emotional. I can’t explain. I have a ‘natural’ image of him…” And she explains why her performances are so different from one to the next:

I always doubt. I’m always groping. “Should I do this or that?” So I try new things, in the same pieces, too. I try not to imitate myself. That’s dangerous. It’s a risk you run if you’re too pleased with what you’ve done, or you get into a routine, because you start to imitate yourself. And that’s the worst...I kind of go out on a limb sometimes, so it doesn’t happen to me.

Gachot sprinkles the production with video of Argerich in rehearsal and performance, playing chamber music, and, mercifully, all by herself. The extras contain nearly 40 minutes of performances: rehearsals of Schumann’s piano concerto, chamber music, and three encores she was persuaded to perform at a concert in 2001, including a Chopin mazurka new her to discography. It’s wonderful, and of course it leaves us wanting more.I wish you luck if you’re trying to see the mercurial pianist in person. I’ve had tickets to see her three times. She cancelled the first time (though a young pianist named Yuja Wang made her debut with a thrilling performance of Tchaikovsky’s concerto). She cancelled the second as well. I finally got a chance to see her this past October at Carnegie Hall. The program was Ravel’s Valses nobles et sentimentales, the first piano concertos of Prokofiev and Shostakovich, and Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition – the orchestrated version of course. Charles Dutoit conducted the Philadelphia Orchestra in all four pieces.Argerich played the two concertos sandwiching the intermission. Evidently she’s learned that when you play the final piece of the evening, the audience will cheer and clap and stomp until you’ve played them an encore. And so we got none, though we certainly tried. The opening Ravel was lush and full-bodied; Dutoit has whipped this ensemble into one of the best in the country. Next came the Prokofiev. The heaving first movement was high drama, the Andante lyrical, and the finale was taken at breakneck speed. A five-minute standing ovation couldn’t get the pianist to come back to the piano before intermission.Argerich in 2005: Prokofiev’s Concerto #1 in D-flat Major, 1st MovementThe Shostakovich concerto would be our last chance. Again the playing was superb, but aside from the Lento second movement, I don’t really enjoy the piece. I suspect many in the audience felt the same way. Shostakovich created an ingenious satire of a concerto, but it doesn’t go far beyond the listener’s brain. The finale is more abrasive than funny. And so I think it’s for reasons other than the concerto that Argerich received another huge ovation, something that simply doesn’t happen when there’s more music to be played. It looked as if Dutoit was encouraging her to play something, but she wouldn’t oblige.The musical highlight of the evening was the final piece, Ravel’s splendid orchestration of Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition, originally composed for the piano. It was a heavy, emotionally charged performance. There are few greater crowd-pleasers in the repertoire, and the audience met it with thunderous applause. But I think part of it was our hope, a futile one of course, that the recluse would burst out of the back stage and give us what we’d been asking of her for the last twenty years. I know that for all the virtuosity of Dutoit and his orchestra, I’d have given almost anything to hear her play the mad Russian’s magnum opus as originally written. We’re all still waiting for Argerich to once more appear without the protection of collaborators; no pianist alive could satisfy so many with a single encore.An encore from 1980: Schumann’s “Von fremden Landern und Menschen”___Greg Waldmann is a native New Yorker living in Boston with a degree in International Affairs.