Jack Spicer on Mars

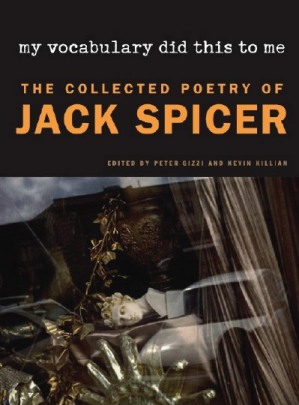

/My Vocabulary Did this to MeThe Collected Poetry of Jack SpicerWesleyan, 2008

“To mess around. To totally destroy the pieces. To build around them.”--from “A Textbook of Poetry” by Jack Spicer

|

“Being dead also wantsFun.--from Billy the Kid by Jack Spicer

Consider the name “Jack.” The poet Jack Spicer certainly did. His poetry, finally available after a long period of out-of-print obscurity, echoes through with references to his own name. A poem of admonition is wryly presented “To Jack;” in another poem the “Jack of Spades” materializes in a deck of tarot cards; in a third, an invocation of Shoeless Joe Jackson reshuffles the syllables into the boxer Jack Johnson, Jacks and Jacksons multiplying in an aural hall of mirrors. Even the poetry journal that Spicer briefly published in mimeograph went by the suggestive initial, J, a mere letter away from the autobiographical I. We may not all yet know Jack Spicer, but we all know Jack. |

Jack, first of all, is not a name exactly, but a slangy nickname, one of those fanciful ones that seems unsatisfied to merely slap a diminutive suffix on its progenitor (like, in this case, Johnny or, less credibly, John-John). Instead, Jack rambles off at a healthy distance, establishing its own wayward domain. Jack is the most anonymous of names – an ordinary name for an ordinary man – but it also has an air of jaunty boyishness, like the orphaned adventurer of a folk tale. It’s a manly, workmanlike name, a name for an honest tradesman of tools: possessor of a jack-knife, say, or a jack-hammer. Yet it’s often a name for a trickster, a crook, a hijacker, a breaker of the rules. Jacks can be sharp, sonically and also by association to knives and other pointy objects like the wobbling jackstones children throw. There’s this kidlike, diminutive aspect to Jack, and also a quickness, a quirkiness, a defiance. Jack is a rude word for literally nothing, “jack shit,” but it’s a negative space that is energized, an electrical jack where you plug something in. It’s a small contraption that can move something large, like a car levered up off its wheels. Jack might be Oedipal, a giant-killer, but he can also be a giant himself, like Jack Kennedy, president, then dead president of Spicer’s nation. In a deck of cards, Jacks seem some hybrid of knights and princes; perhaps they will grow up to be kings. Yet they are not only courtly lovers (the Jack of Hearts) and cavaliers (the Jack of Diamonds). They are also knaves, villains, not to be trusted. Jacks are figures of no small contradiction, and Jack Spicer was, true to his name, a poet of contradiction.

If nothing happens it is possibleTo make things happenHuman history shows thisAnd an apeIs likely (presently) to be an angel.

At the heart of his work is a paradox: Spicer means to produce a “pure poetry” that is self-sufficient, magical and ecstatic, yet he freely draws from his own relationships, his obsessions and interests, his thoughts and fantasies and wishes and swoons. He published his work in his lifetime only in small editions barely distributed outside San Francisco (and even in the city he sometimes avoided major poetry bookstores like Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s City Lights). Yet his poetry seeks a conversation that is culturally wide-ranging and engaged with the publishing world, if in a conflicted, splenetic way. His last book, the posthumously published Book of Magazine Verse, proposes a series of poems dedicated to the major periodicals of the day, none of which would have been likely to publish his work. Most would probably have rejected his submissions, if he submitted at all. Thus, this title dramatizes Spicer’s ambivalence: how would parodic “magazine verse” differ from some other kind of poetry, and how can it remain “magazine verse” when published in a book? Ultimately, Spicer implies, this is a question of integrity, of whether poetry advances a poet’s professional, worldly agenda, or speaks for itself.

Passionately, Spicer sought to avoid a poetry that is commercialized (even refusing to copyright his own poems) or leveraged on ego (he called the personal “a big lie” and began one serial poem, Fifteen False Propositions Against God, with the lines “The self is no longer real”). Yet the voice of his poems is loudly inimitable and always coherent, even as it attempts collage effects and syntactical disjuncture to muss up its surfaces. Spicer is all personality, even if personality is a lie. (The full quotation on this subject is wonderfully ambivalent, like a zen koan: “Nothing matters except the big lie of the personal.”) Spicer’s highbrow and pop obsessions—baseball, Rimbaud, Greek mythology, Jean Cocteau’s Orpheus films, for instance—and even the names of his friends are rendered directly without pseudonym or disguise in his writing. Yet Spicer’s conception of poetry was paradoxically impersonal, imagining the poet more as conduit than creator, partaking of a free-floating poetry that comes from outside and requires mere unbiased, dedicated dictation. If the process is magical, then it is the poet’s job just to get out of the way, and even mistakes like misspellings or printer’s errors or missing punctuation may be integral to the work. His poems are often willfully awkward, for instance insisting on a perverse enjambment in the middle of a word that threatens to annul its meaning, “In- / Ability,” “Limit- / Less,” “No- / Body.” Ever the risk-taker, he even tries in one poem an “I- / Rish.” As if riffing on this element of his poetics, Spicer writes:

When you break a line nothingBecomes better.There is no new (unless you are hummingOld Uncle Tom’s Cabin) there is no newMeasure.You breathe the same and RimbaudWould never even look at you.BreakYour poemLike you would break a grapefruit.MakeIt go to sleep for youAnd each line (There is no Pacific Ocean) And make each lineCut itself. Like seaweed thrownAgainst the pier.

At the same time that Spicer’s poems revel in the mysteries and instabilities of language, they adopt the tone of dramatic soliloquy, proffering pathos, a “woe is me” self-pitying loneliness, as a necessary precondition of art-making. Further complicating the effect, they offer a profusion of proper names: friends, lovers, characters, a panoply of ghosts and smudges that almost seem like company inside the words. His poems are lonely and teeming.

In his book After Lorca, for instance, Spicer summons the Spanish poet Federico Garcia Lorca into a kind of monological dialogue, a duet for one voice. The book includes fairly orthodox translations of a smattering of Lorca’s poems, with some distinctive Spicer poetics mixed in: for instance, a characteristic enjambment after an adverb near the beginning of a sentence, as in “Snow, seaweed, and salt. Now / In the white endlessness.” Here is Spicer’s version of this poem, “Juan Ramón Jimenez”:

In the white endlessnessSnow, seaweed, and saltHe lost his imagination

The color white. He walksUpon a soundless carpet madeOf pigeon feathers.

Without eyes or thumbsHe suffers a dream not movingBut the bones quiver.

In the white endlessnessHow pure and big a woundHis imagination left.

Snow, seaweed, and salt. NowIn the white endlessness.

The poem is mostly loyal to Lorca, though it veers off unpredictably, as with the “seaweed and salt” which in the original Lorca is the loftier nardo and salina, spikenard and saltmine. (Clayton Eshleman discusses these changes at length in his book on translation, Companion Spider.) “Seaweed” and “salt” transforms the line from a historical allusion into something elemental, even Californian. Yet the changes sneak past the reader briskly, as if Spicer were a child hiding under Lorca’s oversized raincoat at a turnstile, getting two for the price of one. Or three, since Lorca’s title refers to his own poetic lineage by invoking the symbolist poet Juan Ramón Jiménez. Then, the circle closes; Juan is Spanish for John, Jack dressed up in camouflage.

|

Not satisfied with tinkering in Lorca’s lyrics, Spicer smuggles his own original poems into After Lorca, also labeled “translations” and sometimes featuring shared imagery or language with bona fide Lorca lyrics, such as Lorca’s “figtree” making a repeat appearance in Spicer’s “The Ballad of the Dead Woodcutter.” (This “Ballad of” poem title also serves as a point of commonality between real and ersatz Lorca poems.) Are we not supposed to know the difference? Unlike Lorca, Spicer’s originals mostly lack regular stanza structures. Spicer labels one poem, “Aquatic Park,” after the San Francisco park he loved to visit, hardly an element of Lorca’s cosmology. Ultimately, Spicer seems less interested in clean verisimilitude than the messiness of influence and inspiration in this “curious amalgam.” Included with the poems are a series of ars poetica letters written by Spicer to Lorca and signed, “Love, Jack.” They throb with fresh authority, acid insight and an undying belief in the transformative essence of poetry: |

|

Tradition means…generations of different poets in different countries patiently telling the same story, writing the same poem, gaining and losing something with each transformation—but, of course, never really losing anything…. Invention is merely the enemy of poetry.

See how weak prose is. I invent a word like invention…. Prose invents—poetry discloses.

Or:

I yell “Shit” down a cliff at an ocean. Even in my lifetime the immediacy of that word will fade. It will be as dead as “Alas.” But if I put the real cliff and the real ocean into the poem, the word “Shit” will ride along with them, travel the time-machine until cliffs and oceans disappear…. Words are what sticks to the real…. The perfect poem has an infinitely small vocabulary.

In the coup de grace of this project, Spicer also includes as foreword a letter purporting to be from Lorca himself, notwithstanding his death in 1936. Somehow Lorca has read these poems and offers his sternly critical and bewildered response from beyond the grave (or somewhere else):

When Mr. Spicer began sending [the letters] to me a few months ago, I recognized immediately the “programmatic letter”—the letter one poet writes to another not in any effort to communicate with him, but rather as a young man whispers his secrets to a scarecrow, knowing that his young lady is in the distance listening. The young lady in this case may be a Muse, but the scarecrow nevertheless quite naturally resents the confidences....

The dead are notoriously hard to satisfy. Mr. Spicer’s mixture may please his contemporary audience or may, and this is more probable, lead him to write better poetry of his own. But I am strongly reminded as I survey this curious amalgam of a cartoon [showing] a gravestone on which were inscribed the words: “HERE LIES AN OFFICER AND A GENTLEMAN.” The caption below it read: “I wonder how they happened to be buried in the same grave?”

The plausibility of the letter is so strong that it would be possible to read it without even getting the joke, imagining Lorca capable of this response to an upstart American taking liberties with his poems. Yet ultimately Spicer seems unable to keep a straight face, and he brings such a spirit of freewheeling experimentation as to give away the game. The poets are like the morbid strange bedfellows of Lorca’s joke, or like silhouettes superimposed over each other: blurred and overlapping, but awkwardly, poignantly, still distinguishable.

Yet it is not exactly a misrepresentation for Spicer to label his own poems “translations,” since his entire project depends upon envisioning the poet as not exactly the creator of his poetry, but rather a passive listener to the poems’ active music, taking dictation upon their arrival. The mysterious, magical source of poems remains in question, a worthy subject for speculation. In a series of lectures in Vancouver delivered shortly before his death, Spicer offered the most memorable narrative: poetry comes as radio signals “from Mars.” Spicer’s Mars evokes a science fiction world of canals and ghostly aliens, a kind of derelict, outer-space Venice of the mind. It also suggests the Greek god of war, hastily re-trained as a radio DJ: violence and danger and blood mixed in the entertainment coming over the airwaves. Spicer liked to use Mars as a code word in his private jokes and games, playacting for children or flirting with friends, sharing a secret identity and a made-up Martian argot. Mars delineates a proud, tender bunker of otherness, a space of alienation and exclusion from the normative project of being an earthling.

Did Spicer actually believe in these Martians, arriving like “spooks” to put words in his mouth? He claimed in the lectures that he was speaking entirely in earnest. His poem, though, presents a bleaker, more equivocal view of inspiration and the drive to speak:

Get those words out of your mouth and into your heart. If there isn’t

A God don’t believe in Him. “Credo

Quia absurdum,” creates wars and pointless loves and was even in Tertullian’s time a heresy. I see him like a tortoise creeping through a vast desert of unbelief.

“The shadows of love are not the shadows of God.”

This is the second heresy created by the first Piltdown man in Plato’s cave. Either

The fire casts a shadow or it doesn’t.

Red balloons, orange balloons, purple balloons all cast off together into a raining sky.

The sky where men weep for men. And above the sky a moon or an astronaut smiles on television. Love

for God or man transformed to distance.

This is the third heresy. Dante

Was the first writer of science-fiction. Beatrice

Shimmering in infinite space.

Obviously, this outer-space fortress of language can only be reached at great expense; ex-lovers and unstable love triangles, loneliness and suffering recur in Spicer’s poems. Spicer himself drank enormous, lethal quantities of liquor, partly as mental and social lubricant, partly as painkiller. In the jauntily devastating “Sporting Life,” Spicer writes:

The trouble with comparing a poet with a radio is that radios don’t develop scar-tissue. The tubes burn out, or with a transistor, which most souls are, the battery or diagram burns out replaceable or not replaceable, but not like that punchdrunk fighter in the bar. The poet

Takes too many messages. The right to the ear that floored him in New Jersey. The right to say that he stood six rounds with a champion

Then they sell beer or go on sporting commissions, or, if the scar tissue is too heavy, demonstrate in a bar where the invisible champions might not have hit him. Too many of them.

The poet is a radio. The poet is a liar. The poet is a counterpunching radio.

And those messages (God would not damn them) do not even know they are champions.

This poem typifies Spicer’s desire to blur the boundaries between poetics and poetry, between a transcendental discourse of the spirit and a colloquial admission of the cost of living. The radio is like that too, an emblem of both futurity and obsolescence. It is the gleaming modernist technology—art deco “tubes” and “transistors”—of Spicer’s childhood, offering the possibility of voices creating a world, like the radio serials that leave the listener always in a state of frustration, wanting to know what happens next. What this translates into in Spicer’s poetry—and what makes his poetry so inspiring—is a kind of license, a willingness to follow the impulse where it leads, to be embarrassing and maudlin and dark and ornery and hopeless and jaundiced. It is his badge of authenticity, a badge of patchwork.

Spicer was ecumenical enough of an agnostic to include even T. S. Eliot in his pantheon of associations, but it would be a simplification to read Spicer’s poetry as merely materializing emotion through objective correlatives. Spicer summons symbolic landscapes, like the overwhelming surf of the Pacific Ocean or the Wild West of Billy the Kid, and crafts evocative figures, like big clumsy animals that seem his stand-ins: a pathetic and hulking “Dancing Ape,” or a “King of the Forest,” who like Patrocles’s lion with the thorn in its paw, complains, “Look, I am in pain. My right leg / Does not fit my left leg.” This is a narrative plight, being stuck with mismatched legs (the word suggests lines of poetry, arhythmic feet, etc.), but the language, with its ridiculous, stolid repetitiveness, undermines the reality of this barbaric yawp. This is not an actual lion that signifies: it is a gesture toward lion-ness, which is to say, it is a language effect. It is to say.

These artificial effects of pathos and bathos are at their most manifest in Spicer’s magnificently torqued use of the word “love” in his poems. Again and again, the monosyllabic word arrives with a kind of promiscuous open-endedness even as it seems always deliberately earnest and lacerating. (Besides “poetry” and “love” the only word that appears to me nearly as conspicuously in these poems is “shit.” This is Spicer at his essence: half-heart, half-spleen.) A whole series of poems in his volume A Red Wheelbarrow are entitled “Love”, “Love II”, “Love III” etc; a series of “Love Poems” appears in his book Language; then there is “Several Years’ Love” in The Heads of Town Up To The Aether. “Love” frequently gets a line all to itself in Spicer’s poems: for instance, “The sounding brass of my heart says / “Love.” Or, “Love, / The Grail, he said…” Spicer uses “love” as a kind of dense abstraction, a linguistic placeholder capable of real action, a communication of an experience that exists almost outside language. Spicer concludes the aforementioned William Carlos Williams-referencing A Red Wheelbarrow book with this mysterious statement: “Love ate the red wheelbarrow.” (Abandoning the aforementioned Roman numeral pattern of II-VII, a characteristic Spicer disruption, this one-line poem is entitled, punningly, “Love 8”). What does this act of eating imply though? Is this a statement about perception, that love can engulf the experience of the real world of wheelbarrows? Is love—i.e., subjectivity, perhaps the replacement of the self with something shared and relational—consuming the impulse to write tiny objective poems like “The Red Wheelbarrow”? To even propose the possibility of an objective reality in which red wheelbarrows appear? The first part in Spicer’s series, “A Red Wheelbarrow” proposes an ethics of objective perception:

Rest and look at this goddamned wheelbarrow. WhateverIt is. Dogs and crocodiles, sunlamps. NotFor their significance.For their significance. For being human.The signs escape you. You, who aren’t very brightAre a signal for them. Not,I mean, the dogs and crocodiles, sunlamps. NotTheir significance.

As always the seriousness of the project seems to waver from moment to moment as the words pass—the tired grumpy “goddamned” leading to the quotidian “dogs” and then the more exotic, fanciful “crocodiles.” All of these modalities, though, seem containable inside the wheelbarrow on loan from Williams. If love “ate” this wheelbarrow, it would make impossible this whole “rest and look at…whatever it is” dictum that is rewriting Williams’s, “No ideas but in things.” Yet it is not only love the feeling, or even the abstract notion of eros that is doing the work here. Rather it is again a linguistic effect, a denoting that points to the “Love” in the title of the poems, and to itself. The word love eats the word wheelbarrow.

This use of the word “love” to energize a poem occurs most powerfully when Spicer expends it in the phrase, “I love you,” which appears several times in his poetry. Writing “I love you” creates an uncomfortable moment (Spicer wonderfully refers to “uncomfortable music” at one point), a kind of Travis Bickle, ‘you talking to me?’ confrontation where it is unclear what is being directed toward the reader, and what is overheard. It is a gesture simultaneously of excess and intimacy. Writing down the words “I love you” creates a situation where no one can ever respond on the page, can ever love “you” back. It’s thus a masochistic act as well, a performance of self-pity, of loneliness at the sound of one’s own voice all by itself alone.

|

Take the poem “For Russ,” which appears in Spicer’s book, Admonitions, a series of poems each written “for” a particular friend or lover in Spicer’s circle of poets and artists. The idea of admonishment that each poem invokes is curiously multifaceted; it is verbal rebuke for errors already perpetrated in the past, it is imperative advice for action in the present, and it is a warning intended to forestall a possibility, to change the future. There’s a know-it-all Cassandra quality to a poetry of admonitions, as the conversational speech act has been moved out of the context where it could have affected the individual toward whom it “originally” was directed. The very nature of a book of admonishments, each memorializing a specific relationship in Spicer’s life, is to stylize the notion of communication, like writing a public letter of complaint to a politician: its publicity is in fact as much the message as its ostensible content. Transfiguring the personal into the metaphysical in this way, “For Russ” is a remarkable poem of equivocation and regret: |

|

Christ,You’d think it would all bePretty simple.This tree will never grow. This bushHas no branches. NoI love you. YetI wonder how our mouths will look in twenty yearsWhen we say yet.

So much weight, as often occurs in Spicer’s poems, is placed on the line break of that “No / I love you. Yet.” By cutting the line there, Spicer creates a hermeneutic uncertainty; is the line break a hidden comma, a retraction as in “No, wait a minute, I do love you” or a statement of absence, the “I love you” turned into an organic object that is absent--that, like those phallic branches, refuses to bloom? The “yet” is equally ambiguous: a yet that is both a hesitation or indecision, a “but…” and also a statement of endurance (“even now, after everything”), or hope ("not now, but maybe in the future”). Should one read “yet” as an admission of failure, the inadequacy of “I love you” to produce the relationship it demands? Perhaps it is the white flag of surrender, a yet that forgives everything, that is the opposite of “never.” The “yet” remains indeterminate and overdetermined as it becomes a singularity, an intimate relic from a memory that hasn’t happened yet, and will not happen. From the vantage of hindsight it is even more poignant: both Spicer and the ostensible Russ of the poem, Spicer’s ex-lover Russell FitzGerald, would be dead long before twenty years had passed. Even at the moment of its writing though, the poem itself existed as an artifact of a relationship that had already combusted, a way of perpetuating a feeling, a love that persists inside its abandonment. The same is true now in the eternal present of reading: “yet” does not have to mean; saying it is what is important.

“Letter to James Alexander,” another poem of excruciating self-conscious intimacy, purports to document a series of Spicer’s actual letters to an actual James Alexander, a younger, Rimbaud-obsessed poet whom Spicer fell in love with as a kind of older, reckless Paul Verlaine figure. (The story is fleshed out in the 1998 biography of Spicer, Poet Be Like God: Jack Spicer and the San Francisco Renaissance, written by Lewis Ellingham and Kevin Killian, co-editor of this new collection with Peter Gizzi.) To create a space for poetry in these letters, Spicer momentarily constructs a dichotomy between “Jim” his friend and “James” the idealized love object, the recipient of a poem as opposed to a letter. One can’t tell whether these are literally verbatim letters or simulacra or even a neurotic form of public erotomania, but each one begins, “Dear James” and is signed, like the Lorca poems, “Love, Jack.” Is this an unauthorized publication of a confidential correspondence? Are the letters real letters, or poems using the letter format as a device, a pretext to speak? What is the reader’s role here? Are we being invited into a ménage trois? Is our presence expected to ratify a relationship that would otherwise be impossible? Spicer writes in one letter, “I read them all (your letters and mine) to the poets assembled for the occasion last Wednesday. Ebbe was annoyed since he thought that letters should remain letters (unless they were essays) and poems poems (a black butterfly just flew past my leg) and that the universe of the personal and the impersonal should be kept in order.” Spicer, apparently disagrees: it is not that the personal and impersonal should be disordered, but that the categories themselves are impossible to maintain.

After all, the Jim-James firewall is untenable. The formal “James” addressee seems not a real person, in any case, but a placeholder for the beloved, a pure conceit, an idée fixe, a godhead like the elegiac Lycidas Milton extrapolated from his dead classmate or the Roman god Antinous, canonized by order of his lover, the Emperor Hadrian, after Antinous drowned in the Nile. Yet James is not deceased, merely absent from San Francisco, and thus he and Jim are equally available as interlocutors; thus, Spicer further confuses matters by muddying the Jim-James dichotomy, addressing some of the letters to Jim. He writes: “Dear Jim, I am writing this letter to you rather than James as it is a Christmas letter and both he and I would find it uncomfortable—like saying Merry Christmas to Rimbaud.”

Spicer delights in these sort of tricks, flipping between modes of high literary, slang and common talk. Orpheus appears in another poem, but as a pathetic clown, a punchdrunk version of Jean Cocteau’s motorcyclist, gawking and “making horrible sounds on his guitar” at the wrong person in Hell. The Grail-seeking knights of Camelot make an appearance, with Lancelot cuckolding King Arthur, but here he is a more prosaic “Lance,” an apparent womanizer less interested in Gwinevere than “Elaine,” who he “fucked… twenty times / At least.” The Grail itself is “as common as rats or seaweed / Not lost but misplaced.” When Sir Galahad, somehow “invented by American spies,” encounters the Grail, it is a cauldron burbling with associations: the humbug Wizard of Oz, the callous, headlong massacre at Gallipoli, and the menacing potions of Alice in Wonderland. Elsewhere in Spicer’s imagination, Prometheus, the sounds of his name wonderfully materialized into “Pro-me-thee-us,” a colloquy of pronouns and a narrative of romantic union (me + thee = us), is just “a guy who had his liver eaten out by birds. A bum who rode a black train.” This eating leads to another paranomastic language discovery: “poetry” becoming “po-eatery,” poetry becoming the site where the violence of eating takes place.

Spicer’s vulgar modernizing of mythologies does not lead to desecration; the poems do muddy up the pristine stories, but as a kind of communion, a way for him to enter the stories in his grossness and in theirs. Poetry, Spicer avers, is a “bordello,” and the worship of beauty is “whorship.” Trash and beauty and creation share the same space, as in “The Birth of Venus”:

Everything destroyed must be thrown away

If it were even an emotion

The seashell would be fake. Camp

Moving in nothing.

Camp partly as the homosexuals mean it as private sorrow

And partly as others mean it—lighting fire for food.

Neither, I said, seawater

Gives nothing.

The birth of Venus happened when she was ready to be born, the seawater did not mind her, and more important, there was a beach, not a breach in the universe but an actual fucking beach that was ready to receive her

Shell and all.

Love and food of

Venus is a travesty in a fake shell surrounded by a nothing that is desperate and bitter. Her beautiful arrival is no gift or message from anywhere or anyone—elsewhere Spicer insists, “The Ocean / Does not mean to be listened to.” The poet is only a paltry beach besides some paltry “seawater.” Even so, the miracle of her arrival is powerful, to be the beach she lands on is strain enough to force from Spicer that excessive, exasperated “fucking.” The last line here, all hope for manna of heaven, ends in a marveling ellipsis, an admission of the abjection of any object, noun or person that would aspire to completing that closing preposition. Spicer remixes Shakespeare’s exhortation “If music be the food of love” but there is no fanfare here, no music. There is a nothing that is beyond even the word “nothing.”

In spite of the depth of work in this new Collected Poetry of Jack Spicer, a few pieces of material that appeared in the previous, long out-of-print collections of Spicer’s poems, The Collected Books of Jack Spicer (1975) and One Night Stand and Other Poems (1980), do not appear in My Vocabulary Did This To Me. (The title refers to Spicer’s reported last words, murmured from near-coma as his body disintegrated from the effects of years of heavy drinking) Among these orphans that will likely appear in future volumes of Spiceriana—Gizzi and Killian plan forthcoming collections of Spicer’s letters and other writings—is a record of Spicer’s responses to a workshop questionnaire distributed by Spicer’s friend and rival Robert Duncan. It’s a revealing document of one-upmanship and erudition that includes a most strange answer to Duncan’s pushy, if thought-provoking, question: “How would you say your physique is related to the form of your poetry at the present point?” Spicer’s even pushier response: “I have anal warts.” It is the inclusion of the unvarnished reality even of these warts in the “uncomfortable music” of his poetry that is so bracing and brave and extraordinary. In the “Love Poems” in Language, Spicer writes, “This isn’t shit it is poetry” and then, later in the same poem, “Going into hell so many times tears it / Which explains poetry.” This is not only the tearing of pages or crying eyes, but the tearing of tissue in the act of touching, of sex—anal sex especially. Spicer continues:

Against wisdom as such. Such

Tired wisdoms as the game-hunters develop

Shooting Zeus, Alpha Centauri, wolf with the same toy gun.

It is deadly hard to worship god, star and totem. Deadly easy

To use them like worn-out condoms spattered by your own gleeful,

crass, and unworshipping

Wisdom

Which explains poetry.

Like Lancelot’s “fucking” or the “honey in the groin” of Spicer’s Billy the Kid for whom death appears as a “Cock with his throat cut wearing a bandana,” these squalid facts, proofs of estrangement and affection, coexist with and constitute transcendence, the numinous such as it is.

|

Among his answers in the questionnaire, Spicer includes a cosmology of his influences circa 1958, including his friends Duncan and Robin Blaser and some usual suspects—Yeats and Lorca and Pound—as well as some surprising others—the Dada artists and an unlikely presiding deity, Miles Davis. I’d actually submit that the closest jazz analogue to Spicer’s clumsy, screwball, pratfalling music is not searing Miles Davis or even Spicer’s beloved Charlie Parker, but rather the ungainly hipster Thelonious Monk, his scales cascading down a piano full of consummate, necessary mistakes. As in Spicer, the errors and the blue notes constitute not only an aesthetic; they are a worldview. Here is the last part of Book of Magazine Verse, which, since this was Spicer’s last book may be nearly the last poetry Spicer wrote: |

At least we both know how shitty the world is. You wearing a beard as a mask to disguise it. I wearing my tired smile. I don’t see how you do it. One hundred thousand university students marching with you. Toward

A necessity which is not love but is a name.

King of the May. A title not chosen for dancing. The police

Civil but obstinate. If they’d attacked

The kind of love (not sex but love), you gave the one hundred thousand students I’d have been very glad. And loved the policemen. Why

Fight the combine of your heart and my heart or anybody’s heart. People are starving.

In this poem, Allen Ginsberg looms as a kind of doppelganger for Spicer, holding forth before crowds with his iconic beard, a poet people actually might listen to. From the perspective of biography, the parallel is intriguing; Spicer left San Francisco for an alienated period in exile on the East Coast shortly before Ginsberg arrived from New York to deliver his famous reading of Howl at the Six Gallery that Spicer helped to found. Years later after they had switched places once again, according to Poet Be Like God, Ginsberg and Spicer had a brief, purportedly unsatisfying sexual encounter at a party. Meanwhile, Ginsberg was celebrated (and celebrated himself) as the “Kraj Majales” in Communist Czechoslovakia while Spicer’s sociocultural dreams went unfulfilled. Indeed, as Gizzi and Killian relate in the introduction to My Vocabulary Did This to Me, Spicer had bravely attended the radical proto-gay rights Mattachine Society convention in the early 1950s and his academic career as a linguist and poet mentor foundered when he refused to sign an official loyalty oath at the University of California at Berkeley. As Ginsberg was surging into the role of King of the May, Jack Spicer was King of the Might But Probably Might Not. Yet this poem suggests that Spicer was more comfortable offstage in the fallen world on an anonymous dais of his own making. There, he could be surer of his integrity pursuing the spirit of “love,” not the making of “a name.”

What would Jack Spicer make of this hardcover edition, thick and official and distributed nationwide, even worldwide? It represents an incredible journey from the cultish obscurity which enveloped his work for decades, in spite of the efforts of his friends like Robin Blaser, who edited the Collected Books published in 1975, and Donald Allen, who included Spicer in his definitive anthology New American Poetry 1945-1960 and edited One Night Stand. These books may have raised Spicer’s profile beyond his circle of friends and fellow barflies in the Bay Area, but both collections have long been out of print. In one of the most hilarious and sad anecdotes in Poet Be Like God, the biographers include a throwaway comment from Ferlinghetti during the interview Killian conducted with him in 1990, “Why would anyone want to publish a biography of Spicer? He’s almost forgotten nowadays, isn’t he?” There is a terrific improbability and a crazy providence in the idea that Spicer’s posthumous editor, Peter Gizzi, would literally be poetry editor at The Nation, one of the magazines that Spicer lampooned in Book of Magazine Verse. I remember encountering the following poem of his several months ago in Harper’s and being surprised, then charmed, wondering what Spicer would think of these words being enshrined in such a bastion of Northeastern liberal establishment sensibility:

Sweet God, it is lonely to be dead. Sweet God, is there any God to worship? God stands in Boston like a public statue. Sweet God, is there any God to swear love by? Or love—it is lonely, is lonely, is lonely to be lonely in Boston.... Sweet God, poetry hates Boston.

Spicer’s poetry is so saturated with the drama of outsiderness that it is bewildering to read him in the role of enthroned master that he both sought and was repelled by in his lifetime. The biography teems with stories of poets not quite understanding Spicer’s mixed signals. Robert Creeley, for instance, inspired a series of poems, “Homage to Creeley,” that adopt Creeley’s cropped, rapid Elizabethan music in Spicer’s voice. Creeley and Spicer even knew each other, vaguely, having crossed paths when Creeley was living in San Francisco. Yet Creeley was reportedly baffled by the poems when he saw them, an event that only occurred years later. Spicer may have sought a theoretical dialogue with Creeley but, full of conflicts regarding success and publicity, it seems that Spicer may have not even sent the book to him.

In this vein, Spicer writes,

The poet is stepping out of the airplane

Dignity is a part of not being asked

*

I miss you, I said. The dead flowers,

The poets who wanted to kiss me, the naked hatred

That wanted to kiss me. I miss their flowers

I miss the hatred of not being asked.

But Jack…

Shut up, I said. Nothing but love could have eaten the roses.

Spicer’s poetry may have been predicated on recklessness and ressentiment, this “hatred of not being asked,” but also, paradoxically, on a poetics of love. It is galling to reach the end even of this gloriously longer collection of Spicer’s poems, which includes many new poems rescued from his journals, gleaned off scraps of paper and in marginalia and even, in one case, found on a map scrawled with handwriting. (The editors, Kevin Killian and Peter Gizzi, cutely label these last pieces “Map Poems.”) We can only be grateful for their efforts and their discoveries.

One of the most enthralling documents Killian and Gizzi include among the poems is the questionnaire that Spicer created for a legendary workshop he offered in 1956, entitled, characteristically, “Poetry As Magic.” It brims with generous, skewed sensibility, posing sly, mock-serious questions like “What political group, slogan, or idea in the world today has the most to do with Magic?” and “What star do you most resemble?” The climactic essay topic is, “Invent a dream in which you appear as a poet.” This might be the cleanest description of Spicer’s practice of poetry: inhabiting a dream, coming to believe it. More than ever, with this new collection of his work, we are now living Jack Spicer’s dream.

____Jared White was born in Boston and has lived in Brooklyn for about eight years, near two big bridges. His poems have appeared in Barrow Street, Cannibal, Coconut, Fulcrum, Harp & Altar, Horse Less Review, The Modern Review, Sawbuck, and Word For/Word, among other journals. A chapbook of poems entitled Yellowcake will appear in the upcoming chapbook collection, Narwhal, from Cannibal Books. He maintains an occasional blog, No No Yes No Yes, at jaredswhite.blogspot.com.