OLM Favorites: Not A Boating Accident

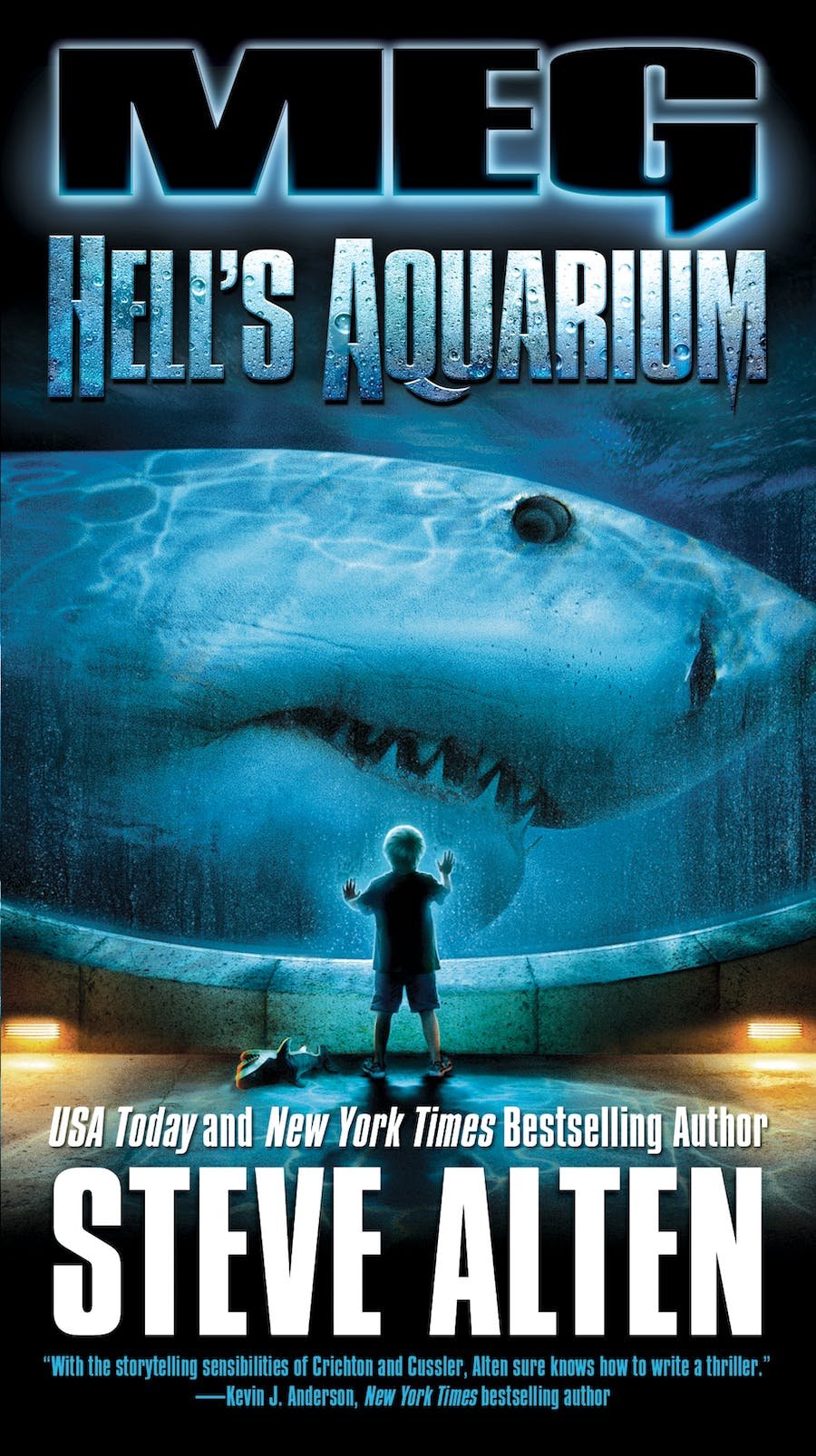

/Meg: Hell's Aquarium

By Steve Alten

Variance Publishing, 2009

Meg: Hell's Aquarium (Volume 4)

By Steve Alten

Macmillan, 2009

It was the perennially underrated John Arbuthnot, so willingly lampooned in The Memoirs of Martinus Scriblerus, who put it best: “The taste of the bathos is implanted by nature itself in the soul of man; till, perverted by custom or example, he is taught, or rather compelled, to relish the sublime.”

If this is true for bathos, how much more true must it be for bathyspheres, and so we come to what is perhaps the central question of modern hermeneutics: can a giant killer shark novel be good? In unraveling the ichthyologic etiology of such a query, you’d expect the ur-text to be Peter Benchley’s 1975 novel Jaws, but that isn’t quite right. Benchley’s novel is actually a very smart, very urbane cautionary tale about human predators, about the voracity at the heart of human concupiscence. It has shrewd characterizations, multiple layers, and long evocative descriptive passages – in other words, in terms of giant killer shark novels, it wastes a lot of time.

Because the important category when dealing with giant killer shark novels is that whole ‘giant killer shark’ part. That the shark be giant is absolutely de rigueur – despite the fact that some 90 percent of annual recorded shark attacks in the world involve fish smaller than basset hounds, such mishaps have zero dramatic potential. The egotism of the victim species adamantly determines the dimensions of the attacker, so sharks have to be huge … in fact, considering the navel-gazing capacity of the human race, it’s a wonder nobody’s written a giant killer shark novel in which the fish has gold-plated teeth.

The ‘killer’ part is the real key, though – it’s certainly the part that disqualifies Jaws. The “great fish” in Jaws kills people, but it’s just doing what sharks do, simply exploring a newly-discovered aisle at the supermarket. In that novel, if Benchley had decided on page 70 to fill Amity Sound with flopping baby seals, his big shark would have swerved clear of gristly humans without a second thought. The important thing isn’t that the sharks in question kill people. Golf ball-sized hailstones and falling terra cotta angels kill people, but they couldn’t be called killers, and by the same token neither could most sharks that swim in and take a bite, even a lethal bite. The dental damage alone isn’t enough – bite radius gets you squat in this town. As Freud might well have said, sometimes a shark is just a shark.

No, the giant killer shark has to embrace the killing. It has to transgress not just the five food groups but the Seven Deadly Sins. This rules out Jaws as firmly as if it had never been written, and it turns our attention rightly to the true source of the modern giant killer shark novel (‘modern’ because both Melville and Poe took faint nibbles at the genre a century ago): Jaws 2, the book written by seasoned, genuinely talented industry hack Hank Searls in 1978. In that story, which takes place a couple of years after the shark ‘Trouble’ of the events in Jaws ended in the destruction of the 22-foot great white shark that had been terrorizing the peaceful beach town of Amity, an offspring of that dead shark, twice its size, returns to the waters off Amity and proceeds to wreak havoc. At the novel’s climax, beleaguered Police Chief Brody, distracted by this new shark’s gourmandizing, lapses into a key piece of hysteria:

Incredible … Not a living creature … A force of nature …He had the nightmarish thought that The Trouble … the shark off Amity Township … had never died at all. He had imagined it, not really seen it slipping dead into the shadows, it was immortal, invulnerable, would be here when all that he knew had left.

Chief Brody is wrong in the short term – he beats the huge shark in Jaws 2 (he gets it to bite down on an electrical cord, so kids, let that be a lesson to you) – but he’s dead right in the long run … literally, since in all subsequent Jaws novels he’s had a fatal heart attack and isn’t around to confront the increasingly more giant, more killer sharks that continue to bedevil his family. Future generations of Brodys have precious little success as shark-stopping heroes, although several of them do quite well as shark dental floss. But by then the germ is planted, the seed sown, the hook baited – by then the immortal, invulnerable shark is already born and swimming toward an isolated oceanic research station near you.

Ironically, actual nature works against the writers of giant killer shark novels, because in the natural world, there’s absolutely no doubt which life-form is the top relentlessly marauding predator on Earth, and it isn’t sharks. In the last twenty years alone, humans have virtually scoured the sea clean of living organisms – including millions of sharks of all species. These sharks are harvested in staggering numbers, shorn of their dorsal and caudal fins (which are used as the key ingredient in a fashionable soup), and tossed back into the sea mutilated and dying. No reliable estimates exist as to the extent of this harvesting, but it’s safe to say there will be no sizeable sharks left in the ocean in another ten years. After which, they’ll exist only in giant killer shark novels – although one wonders if shark extinction will also signal the extinction of the giant killer shark novel. Nobody writes killer buffalo novels anymore, after all.

Perhaps in some kind of unconscious reaction to this imbalance, the writers of modern giant killer shark novels have added one crucial ingredient to the immortal, invulnerable concoction Searls cooked up: science. No longer content to simply broker a Facebook meeting between a fat, bobbing Methodist and a rogue member of Carcharodon carcharias, they’ve set about, yenta-like, insuring such a meeting can’t not happen. Under normal circumstances, the bigger great white sharks get, the more seldom they bother to hunt for food anywhere near the ocean’s surface, where the pickings are comparatively slim. True, off California’s Farallon Islands every year you can find twenty-footers catapulting from the depths to punt baby seals ten feet into the air before chomping them into paintball-bursts of blood and blubber, but those sharks are just showboating dandies. Animals considerably bigger never indulge in gymnastics, preferring to prowl unobserved in the inky black where, presumably, much bigger prey hangs out (ten years ago a documentary team anchored a rotting carcass at 50 feet and filmed what happened, with quietly terrifying results: at first, the bait was worried by a crowd of six-foot sharks, but after a few minutes there came up from below a few ten and twelve-footers who dispersed the smaller fish, until they themselves were dispersed from below by a couple of eighteen-footers, who ate for only a few minutes before you could clearly see a ghostly-grey 25-foot behemoth rising slowly from the depths, causing those eighteen-footers to flee like minnows … and who knows what drove that behemoth away?

We never find out, but only because the 25-footer ate the camera). Such giant sharks seem perfectly content to swim, eat, and die far from vacationing Brodys, and to counter-act such unsuitable bashfulness, killer shark novelists improve on nature in the same time-honored way beauty pageant contestants do: with technological enhancements. Cloning technology comes in hand here (as it might in beauty pageants – who are we to judge?), as first seen in another seminal giant killer shark text, William R. Dantz’s 1992 Hunger, in which the Sealife Institute (there’s always an institute) genetically engineers a batch of killer sharks and clones into them the fun leaping ability of dolphins (the novel was published only a couple of years before we got conclusive video proof that sharks have plenty of natural-born leaping ability, but one senses Dantz would have been undeterred). There are two problems endemic to any giant killer shark novel: first, sharks can only eat you if you go in the water, and second, even in the water, humans still have that great big brain of theirs, sufficient for perhaps outwitting a huge killing machine with a brain the size of a peanut. In his fiendishly inventive twist, Dantz gets around both these problems – his sharks can leap like Flipper, and the very cloning process that gave them that ability also gave them the ability to think like Flipper.

Fortunately for mankind, the giant killer sharks in Hunger are all vanquished by the novel’s end (I think, though I could be wrong, that they’re all tricked into biting down on an electrical wire) – or ARE they? In classic thriller fashion, we’re left with a final scene in which it’s just possible the besetting evil is immortal and invulnerable (this gimmick is widespread throughout escapist literature and is given the definitive send-up at the conclusion of the Buffy the Vampire Slayer episode in which she faces Dracula, where the villain keeps trying to return, to the point where we hear Buffy’s annoyed voice-over saying “I’m standing right here!”).Still, genetic enhancements will only take you so far (except, come to think of it, in beauty pageants): even the smartest, most agile shark inspires no terror in Iowa lakes. In the wake of Dantz’s book, the giant killer shark novel seemed washed up, an evolutionary dead end. Short of giving us sharks who drive land rovers, what could aspiring ichthyothrillers do?

Meg Volume 1 https://us.macmillan.com/books/9781250764232/meganovelofdeepterror

By Steve Alten

Macmillan

In 1997, Steve Alten solved that problem in a quintessentially American way: if something isn’t working, make it bigger and try again. He dreamt up Meg. Short for Carcharodon megalodon, a monstrous 60-foot 20-ton shark that roamed the tepid oceans of Earth’s Late Cretaceous Period, feasting on prehistoric sea-creatures (and, in the opening scene of that first Alten novel, Meg, a lucklessly waterlogged Tyrannosaurus rex). In Meg, Alten imagines a breeding population of Megs that takes up residence in the incredible depths of the Mariana Trench, where they swim and eat and mind their own business, unglimpsed by modern man – except for marine biologist Jonas Taylor, who spots a living Meg while on a deep dive and is greeted with the ridicule of his colleagues when he reports it. As you might expect, a Meg or two make their way to the surface and wreak havoc in the modern world, and in the manner of giant killer shark novels, events conspire to put Dr. Taylor in their path. In the end, he manages to net one alive.

The Los Angeles Times, blurbing about Meg, hit the nail squarely on the head: “Jurassic Shark!” Other critics were less eager to gobble it up, and Entertainment Weekly drolly reported that Alten’s publisher was unhappy with the draft of his second Meg thriller. A lesser writer might have seen blood in the water and paddled to shore while the paddling was good (Alten did swerve from his template, a couple of years ago, turning out The Loch, a very entertaining novel about, um, the Loch Ness Monster) – and perhaps a greater writer would have too. But Alten is at heart a P.T. Barnum-style showman (publicity photos show him spreading his arms inside the fossilized jawbones of a Meg – a stunt Melville would probably have declined), and he must have known that in Carcharodon megalodon he had an absolutely unbeatable gimmick.In his latest Meg novel, the fourth in the series, he’s matched that gimmick with perhaps the greatest schlock-thriller title any such book has ever had. Ladies and gentlemen, surface-dwellers of all ages, welcome to Hell’s Aquarium.Twenty years have passed since the events of Meg. Jonas Taylor, older but still tough as a nut, runs the Tanaka Institute (see?) with his imperious wife Terry (occasionally helped by their children, aspiring newscaster Dani and the novel’s hero, twenty-year-old college football dreamboat David) and his best friend James “Mac” Mackriedes. The Institute’s star attractions come straight from Hell: no less than five Megs – gigantic 60-foot Angel and her five offspring, each of which still dwarfs the biggest great white shark in our modern oceans. As the novel opens, the bleachers are full – and the incredibly predictable happens! Angel bites an Institute worker in half while the horrified audience screams – all except a small group of well-dressed foreigners, who turn out to be from Dubai. The crown prince of that tiny nation (which is real but, as anybody who’s ever visited it will attest, nevertheless feels invented) has built the world’s largest aquatic theme park, and he’s sent his trusted Feisal bin Rashidi to negotiate the purchase of some Megs to attract Western tourists – an uphill process, as bin Rashidi knows full well:

“ … most Westerners will never consider vacationing in our country because of the stigma associated with terrorism and the Middle East.”

Jonas smiles. “Well, at least it hasn’t stopped Haliburton from moving its headquarters there.”

Mac kicks him under the table.

Bin Rashidi’s smile remains frozen. “Thank you for demonstrating my point.”

“My apologies. And you’re right, there’d have to be something pretty special in Dubai to get me to fly halfway around the world to see it, I don’t care how tall your buildings are.”

“On that point we agree. We can also agree that very few people would ever travel to Dubai from North or South America to see a Megalodon when they could simply visit your facility here in California … even if they do risk being eaten.”

Mac winces. “Pick up your jock strap, Jonas, you’ve just been schooled.”

Jonas ignores his friend. “Point taken. So why the visit?”

The Dubai contingent gets down to business: they want to buy a couple of Megs, and they want a Meg specialist to oversee the animals’ introduction to Dubai. Jonas isn’t interested in the job, but if you look closely at his family reminiscences, you might spot a hint as to who his substitute will be: “Wasn’t it yesterday when I held my newborn son in my arms? Coached his little league team? Taught him how to scuba? To pilot a mini-sub? Where did all those years go?”

Where indeed. Turns out young himbo David can’t resist the summer-money Rashidi dangles before his eyes, and as fast as you can say “I’ll be OK dad,” he’s jetting off to Dubai to train the mini-sub pilots who’ll work with the Megs … a group of pilots that includes our hero’s love interest, Kaylie Szeifert, sporting features we’re told resemble “those of a young Stephanie Powers” (it’s not elaborated whether or not that’s a good thing). Kaylie announces herself:

“I’m here to make the cut, and I don’t take prisoners. And before any of you start prejudging me because of my ‘X’ chromosome, I spent the last two summers working at Hawkes Ocean Technologies, helping them test their new Deep Rover submersibles.”

As you could probably predict from that declaration, when crunch-time comes, Kaylie fumbles, panics, blacks out, screams, cries, and needs to be reassured approximately every 16 seconds by strapping young David (David’s sister Dani acquits herself much better in her more limited subplot), who wins her heart despite being callow, coarse, and offhandedly sexist (at one point he coaxes a mini-sub to peak performance while shouting “Hold on, baby, I own this bitch!” – speaking about the sub. I hope). The two of them become a team – and just in time, because it turns out the crown prince has a fiendish hidden agenda: he’s after bigger fish than any Meg.

And here’s where you just have to doff your cap to Alten: in the face of critical mockery and his publisher’s doubts, he took the basic “fish survives the Cretaceous” premise of Meg and amped it up to Meg-sized proportions. In Hell’s Aquarium, which is certainly the best Meg novel to date and quite possibly the best giant killer shark novel ever written, he gives us “the Cretaceous survives the Cretaceous.”

There’s a hidden patch of deep-ocean floor, you see, and there’s a lava-rock roof over most of it, see, and a mad scientist (you didn’t think you were getting out of this without one of them, did you?) discovered it, see, and here’s the best part: it’s got lots of gigantic ancient sea [add: - see - !] creatures in it, not just Megs! And as fast as you can say “I’ll be careful dad,” David and Kaylie find themselves down at the bottom of that hidden sea of monsters, and Jonas is hurrying to save them, enlisting the most unlikely ally imaginable to deal with all those prehistoric beasties (hint: she’s a giant killer shark). Alten writes the whole thing in a hyperkinetic present tense, turns and twists every scene until it squeaks (there’s a scene late in the book involving a shark autopsy that any thriller-writer would give a tonsil to have thought up – I wouldn’t be surprised if Alten danced around the room when it came to him), and takes care to keep his subplots constantly simmering. The whole thing fizzes with the kind of fun delirium only the most effective giant killer shark novels dare to attempt (one of those subplots takes this delirium to utterly unprecedented heights – it involves Natalie Wood’s younger sister Lana, who once upon a time played a Bond girl named Plenty O’Toole)(I am not, needless to say, making this up – I couldn’t if I wanted to).

Which brings us back to the question of hermeneutics, doesn’t it? In Hell’s Aquarium, Steve Alten has written a book that shares almost every quality with its toothsome prehistoric stars: it’s big, not quite mindless, streamlined, ruthlessly effective, and if it ever stopped moving, it would immediately sink out of sight. In it, we see the Hank Searls template in all its details – including occasional flashes of fairly good prose:

Small waves lap the sea wall. Somewhere close by, a metal bracket clinks against a naked flagpole, its hollow cadence set to the wind. The Pacific thunders in the distance. Monterey grays as a storm front moves in from the west.

And most certainly including the ludicrous over-rigging of the enemy on display in Hunger, as when one character, speaking of animal intelligence, says, “If you look at the relationship between brain size and body weight, sharks are right up there with mammals.” Not sure which relationship between brain size and body weight is being referred to here, but if it’s the one connoting intelligence, that character must have taken one too many fin-bumps to the head: sharks are exceedingly simple creatures, entirely incapable of thought (cf: beauty pageant contestants). Only very rarely do their hard-wired behaviors lead them to act like killer-thriller villains (Michael Capuzzo’s slam-bang fantastic 2001 book Close to Shore narrates one such instance and is not to be missed) – the rest of the time, they need a little helping hand from the hardworking hucksters of the writing world.

Steve Alten may just be the best of all those hucksters, and he’s written the Moby Dick of giant killer shark novels. Turn your mind off, open wide, and eat, eat, eat.

Steve Donoghue is a founding editor of Open Letters Monthly. His book criticism has appeared in The Boston Globe, The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, and The American Conservative. He writes regularly for The National, The Vineyard Gazette, and The Christian Science Monitor. His website is http://www.stevedonoghue.com.